Lefteris Kafatos first started studying Japanese at the University of Hawai’i in Manoa. He later went on the Japan Exchange Teaching (JET) Program and was posted in Okinawa. That experience fostered in him a strong interest in language interpretation, and in the nature of the U.S.-Japan alliance. Lefteris went on to study at the Inter-University Center for Japanese Studies (IUC) in Yokohama, where he studied translation and Japan’s post-9/11 defense policies. He also studied Japanese-English Conference Interpreting at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies (MIIS), after which he was recruited to interpret for the U.S. Department of State. It was there his lifetime of struggling in various cultures really paid off. Lefteris also has a Master’s degree in International Affairs from UC San Diego, and today he writes for The Japan Lens, where his focus is the U.S.-Japan alliance, Japanese politics and foreign policy, and regional dynamics in the Asia-Pacific.

(Click on this icon to follow Lefteris: ![]() )

)

Podcast

Transcript

Introduction

Hello, everyone. I am excited to welcome today Mr. Lefteris Kafatos. He’s a wonderful interpreter who’s currently based in LA. He’s someone I look up to as not only a fellow interpreter who’s really experienced, but as someone who’s also delving into journalism through his project called The Japan Lens. He talks about the U.S.-Japan alliance, and has wonderful insight by being at the front lines of the diplomatic relations between the U.S. and Japan. He also interviews high-powered individuals who are knowledgeable about what’s going on between our two countries. Lefteris is Greek American, which I hope he can discuss. He’s also been a diplomatic interpreter and has worked with the State Department, the White House, and all these exciting places that I would love to ask about.

Thank you so much for joining me, Lefteris.

It’s a pleasure, Shiori. Glad to see you.

Childhood and Upbringing

First, I want to start by asking where you were born and raised.

I was born in Colorado, but I don’t have any memory of it because we moved almost immediately to the East Coast. I was primarily raised in the DMV [DC, Maryland, and Virginia] area. We first moved to Maryland, then to Virginia, then to Washington DC, and back to Virginia.

I didn’t realize that you’re a local here [in the DC area]! I understand you’re a second generation Greek American. Could you tell me about that, as well as a bit of your family history?

“Second generation” is open to interpretation, because my parents immigrated separately to the U.S. and were here as students in the 1960s. My father immigrated to the States, whereas my mother was in Canada for a while and later came to the US.

Actually, my grandfather [on my father’s side] took a boat across the Atlantic and arrived at Ellis Island in 1914 when he was 14 or 15 years old. He was in the U.S. for about 14 years and studied at Cornell, but he went back to Greece in 1928, just before the Great Depression.

My father came to the U.S. in 1963 and pursued a doctorate at MIT. He was preceded by my uncle, who also came to study. Both of them were in the sciences.

So that’s a rough and dirty sketch of how my family came from Greece to the U.S.

That’s wonderful that your family has had a long relationship with the U.S., going back and forth. Did you grow up speaking Greek? And did you have any other people around you who were immigrants or second generation?

Yeah, I think my experience as a Greek American was typical of the children of immigrants. My parents made a huge effort to speak English and to assimilate into American society. But they, especially my mother, also had a strong love and respect for their original culture. They cherished it. In the home, when no American friends were around, my parents spoke in Greek. So I was raised in that environment.

I was in Northern Virginia for a large part of my childhood and adolescence. There were other immigrant communities around but not nearly [as much as now]. I’ve been back to where I grew up, and nowadays it feels like it’s much more diverse and multi-ethnic than it was back then. So I did feel a little bit like our family was kind of different from other American families.

Did you struggle with that at all, or did you have other people to talk to about that?

I think it was a pretty welcoming environment. This is a theory I have now as an adult and something I don’t think I was necessarily aware of as a young person, but when you’re a kid you really just want to fit in. And I felt like I didn’t fit in. I don’t think that was because I was bullied or singled out. But there was a little bit of this feeling of not quite American enough, and not quite Greek enough. I feel like that’s just kind of the curse of people who come from multicultural backgrounds. It comes with the territory.

And as for having people to talk to about it, as a young person, I don’t think I even had the awareness or language to talk about it.

Studying Japanese

It‘s really interesting that you had this feeling that something was a little bit off, but you couldn’t even put it into words when you were younger.

I feel like that probably relates to your career, like how you’ve helped connect the U.S. and Japan and other countries. I understand that you first decided to study Japanese when you went to the University of Hawaii (UH), where you majored in Japanese and art. Why did you go to Hawaii, which is really far from the East Coast? And why did you decide to study Japanese?

I really had a strong desire to see the world. As I was growing up, my parents would sometimes take me back to Greece to visit my grandparents and cousins. We also went on a family vacation to Germany once. So it wasn’t unnatural for me to go overseas. We didn’t go all the time because air travel was pretty expensive back then, but [because of that] I had this strong desire to study overseas.

I was kind of rudderless and wasn’t sure what I was going to do, but I was thinking about studying art in Austria. So I was studying German for a while, and I was planning to go on this one-year exchange program, but it ended up not working out.

And the school counselor said, “What about a domestic exchange as opposed to an international exchange?” She gave me this booklet of domestic exchange programs. And in there was the University of Hawaii. I was an avid scuba diver at the time, so I thought, “Maybe I can do that.”

I had always had an interest in Japanese culture. And I could see from the pamphlet that University of Hawaii had an East Asian studies program. It was in this beautiful place. I thought, “Why not?” So that’s how I ended up going to UH Manoa. And it was one of the best decisions I ever made.

As you know, right? Because you grew up there.

Yeah! I had no idea until I got to know you later on that you went to college in Hawaii. I was amazed.

So that’s when you decided to study Japanese. What was the impetus for that?

This was a one-year exchange program, but I ended up wanting to stay past a year. And there was a foreign language requirement. I thought, “Why not take Japanese?” And I absolutely loved it. It was very different from anything I had studied—from Greek, the French I did in high school, and German. I just really took to it. So much so that I wanted to change my major, but ended up not because it would have been the longest bachelor’s degree. So I just continued with my art degree.

What did you like about the Japanese language in particular?

One of the professors that really influenced me in a huge way is still teaching at the University of Hawaii in Manoa. She’s phenomenal. One of the things that I really loved about her class was that the language class was a vehicle for teaching culture.

When we’re learning uniquely Japanese phrases such as “Yoroshiku onegaishimasu,” I think a lot of people just translate that as “Thank you.” But it’s really contextual and specific to the circumstance, right? It can also mean “Nice to meet you” or “I’d really hope that you’d do this for us.”

That was really fascinating. As we’re learning these phrases and going through the textbook, the cultural piece kept opening for me. I think that’s what really hooked me.

Supporting the G8 in Okinawa

After college, you did the JET (Japan Exchange & Teaching) Program and ended up going to Okinawa, which is another very unique location that has so much in common with Hawaii. Could you share a little bit about that experience?

One of the important senseis I had at the University of Hawaii recommended the JET program to me. She wrote me a letter of recommendation. I applied and I got in. Okinawa and Hawaii have a sister-state relationship. So I was in a pretty big cohort of American JETs from Hawaii.

I went there and it was just an incredible experience. There are many Nikkei [Japanese American] folks in Hawaii that have Okinawan roots. And I didn’t realize that until I had been to Hawaii or Okinawa.

I was there to teach English, but eventually my role was shifted to work at the Kencho, the prefectural office in Naha. It was around the time the G8 Summit was going to be held in Okinawa (it was still the G8 back then). There was a lot of preparation in the run-up to that. Part of that required translating letters, meeting with officials from the U.S. military bases. I was shifted away from JET and doing a lot of ad hoc translating and interpreting in preparation for the G8 Summit. Of course, I wasn’t anywhere near able to interpret at the summit, but there were a lot of ancillary events in the run-up to the G8, and so I helped bridge the language gap between Okinawan officials and US officials.

That really goes to show how linguistically talented and hard-working you are. I think a lot of people become ALTs (Assistant Language Teachers) and there are some Coordinators for International Relations (CIRs) [who are fluent in Japanese and work at local government agencies]. But I’ve never heard of someone starting as an ALT and later becoming a CIR. I think people really recognized your talent and wanted to recruit you.

Thanks; that’s generous. I ran into a linguistic brick wall when I arrived in Okinawa, because it’s one thing to learn a language in a class and another thing to actually go in person and [speak].

I think people have this stereotype that everyone is just going to speak in Okinawan dialect. I thought that would be the case. Of course there are such people, but everyone speaks excellent [standard] Japanese.

It’s just that people would speak so fast and I couldn’t catch it. When I arrived, I was crestfallen. People could understand me, [but] I would ask a question and they would rattle back, and I couldn’t understand the answer.

So I really doubled down on my studies at that point. I entered a speech contest for foreigners. I didn’t make the cut the first time, so I entered again and I think I got third or fourth place. I tried to get comfortable with speaking.

It was just an incredible experience for me. I was so lucky to have Okinawan and Japanese friends and colleagues who were so supportive. I would ask, “What does this mean?” or “Why do you say this?” And they taught me and helped me so much. I was really fortunate to have that experience in Okinawa. Okinawa still has a really warm place in my heart. I wish I could be there more often.

Amazing!

Pursuing Interpretation

I wanted to ask about how you fell in love with interpretation, which I understand was when you supported an interview between former kamikaze airman and some journalists. Is that correct?

Yeah. So I ended up staying in Japan for nine years. After JET, I really wanted to be a translator. I wanted to do Japanese to English translation. I studied for a year in Yokohama at the Inter-University Center (IUC), another excellent institution. It’s an incredible program run by Stanford University, and one of the top-notch schools for tertiary-level Japanese language study. After that, I got a job as a translator, and ended up returning to the U.S. in 2006.

I was working for a bilingual Japanese and English newspaper in San Francisco. I was kind of a translator and journalist, and one day my editor sent me out to cover the screening of a film called Wings of Defeat.

The director and filmmaker was a Japanese American individual who wanted to learn more about her family’s involvement in World War II. She found out that she had an uncle or great uncle who had been in the Special Attack Unit, which Americans call kamikaze. So two of these survivors were at the screening in San Francisco, and I went there to cover the event.

I think they didn’t have interpretation set up and I was among a bunch of other American journalists. So I did some interpreting. I did not do a good job. It was better than nothing. They were talking about military ranks and all those things we [interpreters] struggle with. If I had prepared for it in advance, it would have been better. But I was able to help in some way. Even in my clumsy, poor interpretation, I was still able to convey some of the core messages of their story.

I think a lot of Americans still think kamikaze were fanatics who were brainwashed. And hearing these people tell their story, you could actually see that these were unbelievable circumstances, and that these people were trying the best they could.

I just played a small role in that, but it really felt meaningful. So that’s when I decided to go to the Monterey Institute (now called the Middlebury Institute) in Monterey, California to study conference interpreting. I decided to try to become a professional interpreter.

Sounds like it was another life-changing moment!

Among the many different types of interpretation, why did you decide to pursue diplomatic interpretation? And to the extent that you can, would you mind talking a little bit about your time with the State Department after that?

Yeah, it was a crossroads for sure.

The Monterey Institute did a career fair for all the soon-to-be interpreters and soon-to-be translators. The U.S. Department of State Office of Language Services came to speak to promising linguists and recruit them.

The thing that really hooked me was that the State Department staff were telling us about public diplomacy programs, especially the International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP). I don’t know if there’s some uncertainty surrounding their future now, but I think it’s really one of the best public diplomacy programs in the world. That was something that was very attractive to me.

They invited me to take their interpretation tests, and I passed. And they were eager for me to start working in public diplomacy. I had a stint as an interpreter for the Honda Motor Corporation, at Honda Research and Development. But my experience at IVLP made me think, “This is it. This is really where I want to serve the country.”

Eventually, a position opened up [in the State Department] and I applied for it. I became what’s called a diplomatic interpreter, a full-time federal employee. That happened back in 2015, so 10 years ago.

There’s the public diplomacy type of interpretation and there’s the government-to-government diplomacy. These are pretty different. With public diplomacy, you’re interpreting between individuals. They represent their country to some extent, but they’re not officially recognized representatives. So it really is people-to-people diplomacy.

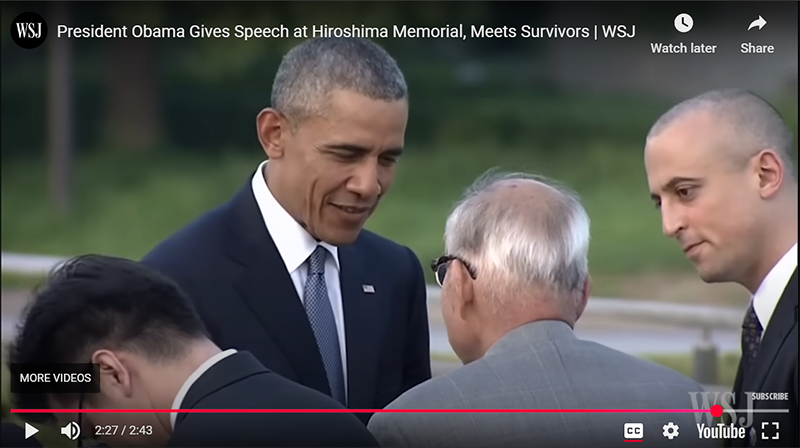

But the government-to-government diplomacy is between officers of both countries. When I started doing that work, it opened up a whole new dimension of interpreting, because there were these big meetings such as President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima in 2016, and Vice President Pence’s economic dialogue with Deputy Prime Minister Aso in 2018, and President Trump’s visit to the Imperial Palace in 2019.

Staying Calm at High-Level Meetings

I wanted to ask about government-to-government interpretation, especially among high-level or high-powered individuals. Once I start interpreting, I calm down a little. But during that moment of silence before the meeting, when we’re all waiting for the principals [i.e., the main speakers we are interpreting] to come into the room, I tend to work myself up and get really nervous. I tell myself, “It’s OK because they’ve hashed it out on the working level [before the meeting], and later on, they will hash it out again. It’s not a big deal if I make a mistake or two,” [but I can’t help it].

You always seem to have a calm demeanor in the photos and videos of you interpreting. Do you have a trick to not become nervous when you’re interpreting at such a high level?

Come on, you worked with me. You know all my shortcomings and weaknesses!

You’ve got to be a bit nervous, right? If you’re just phoning it in, thinking, “I’ve got this,” you’re in trouble. A healthy degree of nervousness [is good]. It’s that sweet spot where you say, “I’m here, I’m ready,” but you’re not keeping the needle in the red too long.

I think what you said is great. There’s this misconception that diplomatic interpreters have to be perfect. Maybe we don’t hear or catch a phrase, or we catch it but flub it on the output. That happens. And of course, we train relentlessly over and over again so that we don’t make those mistakes. There’s the short-term preparation before the assignment, and there’s a long game of preparation.

But there’s no perfection. There’s just the perfect effort in that moment. So when I’m in that situation, I just think back, “Did I do everything I could to prepare for this assignment?”

When I was younger, doing everything I could for an assignment would have been staying up all night and studying. Now that I’m older, I don’t think that way.

If I did everything I could, then I just breathe. Deep breathing [is effective].

I also do the best I can and then just leave the results [for others to judge]. Especially early on, when I had imposter syndrome or felt that somebody else could do this better, I kept thinking, “I’m not good enough.” There were these voices in my head. Now I say to myself, “Yeah, that might be true. [But] let them decide.”

If there’s a National Security Council official who speaks fluent Japanese and is in the meeting listening the whole time—that person can come to me and say, “I don’t think this is going to work out.” But I have too much going on. I can’t objectively judge whether I’m going to be OK. So I just breathe and do the best I can. I’ve told myself that many times: “If it’s not going to work out, they’re going to let you know.”

Thank you so much. That’s really helpful. The deep breathing, and I especially love your phrase, “perfect effort.” There’s so much that happens during interpretation that you cannot control and you really have to learn to let go in the moment.

Studying International Relations

[Eventually,] you decided to leave your full-time position with the U.S. Government. You decided to move to California and pursue another master’s degree in international relations. What was the impetus behind all of that?

I was so fortunate to have my time at the State Department working at the Office of Language Services. It’s such an incredible group of professionals, different people from different backgrounds all pulling in the same direction for the sake of American diplomacy. It was just an incredible experience.

But when COVID hit and the lockdowns happened, most of my family had moved to California and I was stuck in DC. I couldn’t even get on a plane. Things like that started to become part of the consideration. We needed to be closer.

Also, as I was interpreting at these different diplomatic events, meetings, and summits, I had a really strong desire to understand the issues better. For example, if somebody was talking about AUKUS—the Australia-UK-US agreement about submarines—I wanted to understand it better. Or I wanted to understand what exactly happened and why at the Plaza Accord in the 1980s. So that desire to learn more about things was part of the impetus behind going back to school.

I was very fortunate to go to the University of California, San Diego. I got an advanced master’s degree in international relations, with an emphasis on security of the Asia Pacific. And I focused most of my studies and research on the U.S.-Japan relationship.

Breaking Misconceptions through The Japan Lens

Two years ago, you started The Japan Lens. I don’t know how you find the time to do all of that on top of your interpreting work. You interview experts in various areas like Glen Fukushima. But you also write long, detailed analytical articles about what’s going on in the news. You release them in both languages, maybe a day or two after the news comes out. I’m really amazed by that.

Could you talk about why you started The Japan Lens and what you do?

Thanks for reading it. You’re probably one of ten people.

Haha, that’s not true!

One of the things that’s most interesting to me is having frank conversations with my Japanese friends, colleagues, associates, or even people that I don’t even know very well, just talking about the U.S.-Japan relationship.

I feel that there are misconceptions on both sides of the Pacific. There’s this view of America that exists in the Japanese psyche or popular opinion that may have been formed by Hollywood movies or key events that happened in history. So I don’t know if America is accurately viewed in the Japanese mind. Sometimes I feel like it’s not. People ask me things about the U.S. or the U.S. political system and I just want to say, “Well, why don’t we talk about it?” And so I’ll write a Japanese article about what’s happening in the U.S.

Similarly, sometimes Americans or non-Japanese friends will ask about Japan. This becomes very humbling, because I lived in Japan and studied Japanese, but we’re talking about a rich culture that has thousands of years of history and has evolved over the centuries. So it’s still an exciting and new thing for me. I wonder, “What is going on over there?” So I like to write about Japan in English for English-speaking audiences.

There are a few big things [that I’m particularly focused on]. One is that there are a lot of discussions in the U.S. by experts who talk about Japan. But I feel like the Japanese voice is lacking in the discourse sometimes. So one of the big motivations of doing those interviews is to hand a microphone to Japanese people.

Another thing is that I want to challenge some of the assumptions about the U.S.-Japan alliance. I think in America, unfortunately, there is this kind of mindset of like, “Well, Japan’s not a threat anymore. Japan’s a friend. We’ve kind of solved all of the Japan-related problems. It’s no longer a military threat to the U.S. It’s no longer an economic threat.”

And the mechanisms or limbs for trying to understand and get to know Japan better are atrophying. They’re withering away. I think it makes for sloppy assumptions about the U.S.-Japan alliance. I think in some ways, the U.S.-Japan alliance is a lot more fragile than people think. So that’s another purpose of The Japan Lens.

The third thing would be that there’s a lot happening in and around Japan, the East China Sea, East Asia, the Indo-Pacific. And looking at those issues from a Japan perspective is another thing that’s important.

Protecting and Strengthening the U.S.-Japan Alliance

We’ve talked about the U.S.-Japan alliance and how you studied security for your master’s. I was struck by the fact that you were in Hawaii and Okinawa. You also mentioned that one of the most memorable moments working for the U.S. Government was when you accompanied President Obama in Hiroshima. All these places are relevant to World War II and peacebuilding. Is that what led to your interest in security relations?

It definitely had a big part to play.

Speaking of stereotypes and misconceptions, when people look at Okinawa, they tend to say, “Okinawan people are against the U.S. bases. It’s this left-leaning, China-friendly area.” The reality is much more complicated. In fact, I think opinions about the bases in Okinawa are shifting as we speak.

One of the things I experienced in Okinawa was seeing the relationship between locals and the U.S. bases. Whether it was U.S. military personnel or civilians or local Japanese people working on the bases, I was able to see that dynamic. It’s not possible to observe if you just go and visit Okinawa as a tourist. I lived there for four years and saw things in a different way.

This definitely piqued my interest, and I started to question blanket statements such as “Okinawans are like this.” Actually, it turns out, not so much.

When I went to study in Kanagawa at the Inter-University Center, I had to write and defend a thesis in Japanese. I did mine on then-Prime Minister Koizumi and his shifting policy with regard to the Bush administration in the post 9-11 world.

So yes, I’ve been interested in this for a long time, and the defense and wartime histories of these places where I spent a lot of time probably did have a big effect on my interest in defense and the U.S.-Japan alliance as a whole.

I think the U.S.-Japan alliance is more important than ever. But right now, I think it’s fragile, as you said, because there’s so much going on in terms of economic relations and the tariff situation. I think these tensions are unfortunately spilling over to the general public. So how would you speak to the Japanese public who are worried about economic relations, as well as how they might affect our security relations that have been strong until now?

That’s a great question. I think, in more conventional times, there was this understanding that security and economics are separate. Those days are gone. Everything is on the table when negotiations begin.

I think Japan has a strong case to make for saying, “Listen, we’re a good partner.”

For example, if there are criticisms about how much the U.S. bases cost. Japan pays upward of 75 percent, if not more, of the costs. Those bases aren’t only for the sake of Japan’s defense. They also allow for American influence in the region.

It’s also important to tell the story of how many Japanese companies come to the United States and are good employers of Americans. These are companies that are investing deeply and in a long-term manner in American communities. So that’s a strong story that Japan can tell.

As for Japanese people losing faith or questioning the relationship, there was an American politician who said that a treaty is just a piece of paper. It’s the relationship that counts. What looks like an ironclad security treaty today could just be a piece of paper tomorrow.

If we look at the actual relationship between the two countries, it is very strong. There’s never been a stronger interest in the U.S. for Japan. Not just pop culture like manga and anime, but a much broader interest. There’s much more interest in tourism to Japan, although of course, some of that is due to the depreciated yen. People have a very positive opinion and view of Japan.

But they also have a somewhat outdated and maybe inaccurate view of Japan. So this is an opportunity. I think now we’re seeing an opportunity for more exchange between people. You mentioned Glen Fukushima [who studied in Japan and is a strong advocate for study abroad programs between the two countries]. Japan used to send the most exchange students to the U.S. But in a very short amount of time, Japan has become much more insular.

On both sides of the Pacific, we need to ask, “Is this an important relationship? Is this mutual defense treaty important?” Let’s reassess and reevaluate.

And if the answer is yes, then act like it. Invest in those exchange programs. Not just tourism, but actually living in each other’s countries, learning each other’s languages, and experiencing firsthand what’s good and bad about each country. There’s no substitute for that kind of long-term investment in the U.S.-Japan relationship.

Japanese people are looking at things like the failed Nippon Steel acquisition of U.S. Steel or the tariff threats, and feeling disillusioned about Americans. Well, Americans are feeling disillusioned, too. We’re in this state of flux right now. We don’t really know what’s going on.

So I think it’s more important than ever to be curious, reach out to each other, and have those conversations and exchanges. Not just [getting to know] pop culture like manga, anime, and Hollywood films on the surface level. Let’s learn more about each other on a deeper level.

Thank you. I think what you’re doing with The Japan Lens is so incredibly important in that sense, because there’s so much information out there that it’s hard to discern on your own what’s true and what’s important to you. What you’re doing in terms of condensing all of that and making it into content that’s easier to understand, as well as giving the mic to Japanese people who haven’t had the spotlight recently, is really helpful.

Keeping a Curious Mind

Would you have any advice for others who have ties to multiple countries and may be struggling with their identity or figuring out their career?

And I wanted to circle back to what you said about growing up Greek American. You felt like something was off, but you couldn’t quite put it into words. Are you comfortable now with who you are? And what sort of advice would you give to the younger generation?

Gosh, you have great questions. I think, yes, I’m much more comfortable.

There was a time when I swung from extreme to extreme. There was a period when I was a kid and I was just embarrassed of my parents and their accent. I wanted them to stop speaking Greek and speak English. And then I went the other direction.

Now I know who I am. Of course, it’s always challenging navigating those two cultures. As the Stoics say, “The obstacle is the way.” You have to lean into it.

For example, there was a period where I really wanted to add Greek to my language as an interpreter. And eventually I had to set that aside, because there wasn’t a need for it and it would require a lot more time and effort than I was able to put in.

But I made the decision that it is important for me to understand my roots and be active in that. This is a personal choice for people who have a multicultural background. I wanted to spend time reading books and delving deeper into my family history—not in English, but in Greek.

I have encountered individuals who say, “That’s my parents’ stuff. I’m going to go this way and focus on one language and one culture.” That’s a defensible choice because it is so challenging to have one foot in each culture.

But for me, I have to continue that connection with my culture, even if it’s not directly relevant to my work. It’s relevant to who I am as a person.

I would encourage people who wonder, “What should I do about this?” to keep a curious mind about your country of origins, history, and your culture. That’s important because it’s part of who we are.

If you’re interested in bridging the gaps between cultures linguistically, I think there’s still a place for us in the future.

Because of how the interpreting industry is changing, I always tell people that they should have the “plus alpha” model. You have your language skills, your intercultural competence, plus the thing that you’re really interested in. “I’m just a language person” is not going to cut it anymore.

For example, if you’re really interested in Japanese or American filmmaking or a certain genre of literature, really dive into that and also work on your language skills. I think that’s going to be the deciding factor in the coming 5, 10, 15 years.

And a certain degree of tech savviness as well, being able to use machine translation and machine interpretation, and look at it and say, “You could use this AI system to do your interpreting. Here’s where it works. Here’s where there are lot of drawbacks to that.” And be able to speak intelligently about that, because the cost [difference between humans and AI] is not a negligible factor.

We now have to navigate this brave new world as language professionals. And I think that young people absolutely shouldn’t believe the hype that it’s all going to be automated away in AI. No, it’s not.

And there will be this commodification of language services. I think that is going to be inevitable. And I think it’s going to be stratified, like, higher paying customers will get a higher quality machine output, possibly augmented with a human presence. I don’t know exactly how it’s going to look.

But there is always going to be a need for people who have a multicultural, multilingual mindset, especially those people who want to make connections. There’s always going to be a place for such people.

Thank you so much for that insight. I think people like us are used to looking at things in multiple perspectives. So we’re probably a little bit more open to seeing diverse ideas or learning new languages. And I completely agree that despite the technological advances, we will still have a lot of different ways to apply those kinds of insights and talents we may have to all these different jobs.

I also really admire you because you have this interpretation job, but you’re also doing this personal passion project that’s more about expressing yourself and writing. I feel like we have a lot in common and I would love to continue to learn about that. Thank you for sharing all of that with us.

Sure thing. I’m going to learn from you as well, so we’ll continue that going forward.

Thank you. Is there anything you’d like to add or anything I missed?

No. This has been a really great conversation and I appreciate your time. Thanks for having me on your show.

Thank you so much!

Postscript:

After the interview Lefteris and I delved a little deeper into the concept of “perfect effort.” He said: “Effort has also been part of my experience as a Greek-American. As a young person I struggled with my heritage. Sometimes I tried to shun it, other times I tried to learn everything I could about it. Neither of those extremes were good for me.”

Today, Lefteris makes efforts to keep his parents’ language alive in him. He reads books in Greek and tries consistently to communicate with his family using the language. Making such efforts, he said, “is not an entirely logical decision,” but an important one nonetheless. “I’ve given up on trying to be the absolute perfect native speaker of Greek,” he said. “Instead, I strive for the perfect effort. Which is just another way of saying, I strive to keep trying.”

Leave a Reply