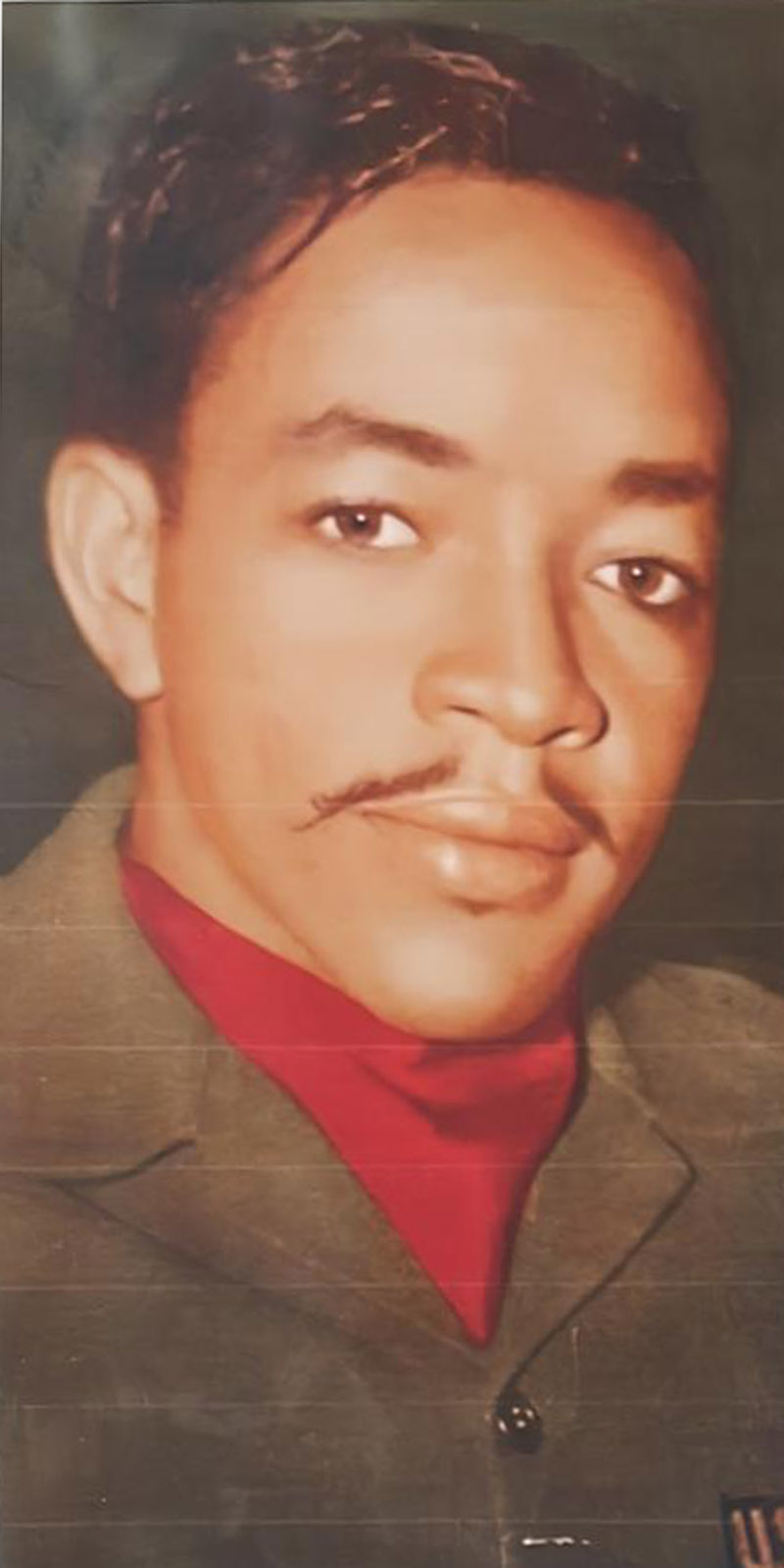

Robert Holloway (who also goes by “Meramsu”) is the son of a Korean adoptee, a descendant of Black Wall Street business owners who survived the Tulsa Race Riots, and a Korean simultaneous interpreter. He didn’t grow up speaking Korean. He learned because of his interest in his family’s history. Robert’s mother was adopted from South Korea in the 1960s to an African American family in Alaska. This led him to a long journey of travel, struggle, joy, and embarrassment in order to speak Korean as fluently as he does today. When he first sought to learn more about interpreting, he was told that it’s “a pipe dream” for him and that he should find some other work to do. Robert kept pushing his Korean language skills until he was able to interpret in court and then even in international conferences as a conference interpreter. Since then he’s interpreted the voices of U.S. President Joe Biden and members of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and has interpreted for Korean Member of Parliament Ji Seong-Ho and more (apparently, there was something inside of that pipe).

(Click on these icons to follow Robert: ![]()

![]()

![]() )

)

Podcast

Transcript

Introduction

Hello, everyone. Today, I’m honored to welcome Robert Holloway. Robert is a Chicago-based Korean interpreter and entrepreneur. His mother is an adoptee from Korea. What’s wonderful about Robert is that not only has he focused on his own heritage by studying Korean, he’s also become fluent enough to interpret in various high stakes environments. And he’s also been supporting other adoptees from Korea who want to improve their language skills. I’m looking forward to hearing about his identity, both as a language professional and as a multicultural individual.

Thank you so much, Robert, for joining me today.

Thank you for having me, Shiori.

Family Background

First, where were you born and raised?

I was born and raised in Seattle, Washington, up in the Pacific Northwest in the United States.

Would you mind talking a little bit about your mother and how she was brought up?

Of course. People often ask me about my background, and I have to start with my mother’s story. My mother was born in South Korea in the 1960s, and shortly thereafter was adopted to Alaska, by an African American family.

To give some background, after the Korean War from 1950 to 1953, the first Korean president was very adamant to send any children that are not full-blooded Korean back to their father’s country. That was his policy at the time.

So starting from the 1950s, the first wave of adoptees were sent back to the United States. As time progressed, those numbers increased.

By the time the 60s hit, my mother was also part of that, her father being American and then her mother being Korean. Her father was an African American GI who was stationed in South Korea and then met my mother’s mother. They conceived, and the story from the adoption agency was that he had a reason to go back to the United States. They had planned to get married, but on his way back to Korea, he passed away in a traffic accident.

Oh no!

And because of that situation, our mother’s mother decided to put her up for adoption. My mother was about two years old at the time.

That’s how she ended up in Alaska and was adopted to an African American family that lived there, which is really unique and peculiar. For one, there weren’t a lot of African American families adopting, at least from Korea that I’m aware of. It was mostly white Caucasian families, especially in the United States Midwest.

She also had an older brother who was also half Black, half Korean and adopted. And they had a younger brother that was adopted as well. So they grew up there together. And when my mother was around 17 or 18 years old, they all made their way to Seattle. She stayed there and eventually met my father, and then I was born in Seattle.

That is fascinating. And the fact that they were adopted by a Black family in Alaska—as you said, I’m sure that’s really rare. I’m sure that culture has been ingrained in your mother.

Yeah, absolutely. Being adopted so young and not into a Korean-centric family, she didn’t really pick up the culture. Outside of “Hello,” she doesn’t speak Korean. She’s more involved with Black American culture.

|  |

Studying Korean

Growing up in a household where you didn’t have a lot of touch points with Korean culture, how did you decide that this is something that you want to look into, such as learning the language, studying abroad there, etc.?

My mother had a keen interest in finding her parents, especially her mother. When she was around 16, 18, maybe 20 years old, she started her adoption search. She was reaching back to newspapers in Korea and the adoption agency, to try and get more details and continue that search.

I have siblings as well. When we were growing up, she would often emphasize, “We have family in Korea. We haven’t found them yet, but just know that we have family there.” She’d have my older sister in Korean school, and she would always impress it upon us to never forget the culture and try and learn more.

It would be to the point where we’re eating American food at home, like hamburgers, fries, salad, and she’s like, “Use your chopsticks.” We’re like, “This isn’t quite the food for chopsticks.” “It doesn’t matter. Use your chopsticks.” “Okay, okay.”

Wow!

By the time I turned 18 and was preparing to graduate high school, at that point, everyone is making decisions like, “When I go out into the world, how am I going to benefit society? How am I going to change the world? What am I going to contribute? What am I going to do?” Some people say marketing; some people want to become a lawyer or a doctor. The only thought that I had was, “I want to do something with this Korean stuff.”

From that point on, I started studying. I briefly attended the University of Hawaii. And after a year or year and a half, I’m telling myself, “If you want to learn a language, you just go to the country.”

So I made the decision to move to Korea for about a year. I went to a language academy focused on learning Korean language and culture. And once I graduated from there, I moved back to the States.

While you were in Korea, did you face any hardships? Would you mind talking about that?

No problem. There are a mix of things. A lot of people encouraged me as someone who is dedicating a large part of their life to learn the language and the culture, and were very happy and welcoming after finding out about my mother’s history.

So I’ll meet somebody, and first they’re kind of blown away because of the level of Korean that I speak. After that, the questions start to come out: “How did you learn Korean? Why are you learning?” Then we get into the history about my mother. And then it’s like, “Wow.” And then people really show respect and reciprocation to the respect that I have for the culture, if that makes sense. If you show a language and a culture respect, that’s reciprocated. That’s one thing that I learned there.

A lot of people took good care of me. I was treated well. And then there were also situations where because I’m foreign or because of—I can’t really say my skin color; I’m not too far off from Korean skin color—but because I’m a foreigner, because I’m different, because I’m African American, there were some situations of racism. It was a mix. But when I left there, [I could say that] I had one of the greatest experiences of my life.

That’s wonderful. And you’ve gone back since then?

Yes, I’ve been back maybe four or five times, and we’ll continue to return annually.

So it’s like your second home now.

Yeah, absolutely.

Family Legacy

I don’t think I heard whether it was resolved: was your mother able to find her mother?

So this is really where we get into the meat of our story. Remember how I told you the adoption agency told us that our mother’s father had passed away?

A few years ago, I visited my mother and asked her to do a DNA test as part of this family search. She was searching for so many years and passed the baton to me, because she saw the affinity and interest that I had in Korean culture and finding family.

Every time I returned to Korea, I spend time trying to find our mother’s mother and that side of the family. We’ve contacted the adoption agency. We’ve gone to the place where she was born and visited the city hall. She’s appeared on Korean TV—all of that. So anyway, she did a DNA test on ancestry.com here in the States. And one of her cousins popped up from her father’s side.

So we got in touch with them, we communicated, and eventually I went and visited them. And fortunately enough, the cousin that we were in contact with was—you know how every family has someone who knows all the family stories and keeps all the records?—he was that person. So he knew everything.

We weren’t sure who my mother’s father was at the time because the family was large. Here’s the wild thing. In my mother’s father’s generation, there were seven or eight men, all Black Americans of similar age. And every single one of them was in the military. Now, in the 60s and 70s, the United States was at war in Vietnam. So if you enlisted, you were sent there. Vietnam was hot then. But each and every single person who enlisted from our family was sent to Korea. I have no clue how that happened.

Through records, we narrowed down and identified who in the family was our mother’s father. And then we discovered some more interesting things about his story. And it turns out that he did not pass away when the adoption agency said that he did.

What!

He was alive for an additional nine years and passed away in California. As we explored further, we found that he had introduced my mother’s mother, his fiancée, to his family back in the United States. Not in person, but through letters or phone calls back and forth, which means that he had a vested interest in continuing that relationship and even bringing his new family back to the United States.

However, according to the military records, he suddenly left Korea and moved to California. His family is all the way on the East Coast. He lived the rest of his years in California, and did not contact anybody in his family. Everyone thought he was ambushed and died in some war because they didn’t hear from him.

Oh my goodness.

And according to his death certificate, it was a liver disease, which means essentially he drank himself to death. What happened for somebody to have a family and then leave, not contact them, and drink until they pass away?

Fast forward a couple of years, and last summer, I attended a conference by the name of IKAA (International Korean Adoptee Associations). It’s the largest Korean adoption conference in the world. It only happens like every three years. So I go there to present and talk about speaking Korean.

This is so crazy. The first night that I’m there, I meet two people who were born in the same town as my mother. One who was maybe like a year apart from her and the other one who was about like 10 years younger than her. Both of the ladies are mixed. They’re half Black, half Korean, just like my mother.

The younger one was telling me her adoption story, and it lined up almost perfectly with my mother’s. But what really made the hair stand up on the back of my neck was that she told me that her father tried to bring his new family from Korea back to the United States. But different discriminatory and racist policies at the time made it so difficult for GIs to bring families that they made overseas back to the United States. Essentially it was blocked. It wasn’t able to happen.

And the fact that I ran into this lady at that time, that for me was confirmation that that’s exactly what happened with my mother’s father. What other tragedy could there be for someone to do that? To go and then not contact their family for almost 10 years, live out the rest of their lives by themselves, and essentially drink themselves to death? That, we discovered, was the history of my mother’s father’s side.

As far as my mother’s mother’s side, we’re still searching. And the next step is to do a Korean DNA test, which they have for Korean adoptees nowadays.

That is amazing. I was really excited when you said that he didn’t pass away when the adoption agency thought he did. It must’ve been even more heartbreaking for all of you because it turns out there was a window, but it was just not possible to meet him while he was alive.

In a way. But it also provided closure. I don’t want to say closure . . . It provided a step to a new beginning, because we found this whole side of the family, and they were very welcoming and happy to know that we were here.

And one more thing is, when I discovered about all of my uncles who were in the military, and the world somehow found them in Korea–that’s when I knew that this affinity or interest or deep passion that I have to learn Korean is not an accident. It’s something that starts from before me.

Which is wild because it’s on both sides of the family, it’s not just my mom’s. Two years ago, there was a family reunion on my father’s side of the family. And one of the cousins is taking out old pictures from different weddings and pictures taken on the street of family members that have passed away. And one of the pictures was from my grandfather’s brother’s wedding.

There’s probably like a good 40, 45 people in the picture. My grandfather’s brother and his wife are in the center and then you have people surrounding them. I look at the bottom right of the picture and there’s this peculiar Asian man. And I asked my cousin, “Who is that?” And he said, “He was the chef and he was good friends with your grandfather. He cooked the food for the entire celebration. His name was Hotak.” I said, “Hotak? Okay, that is an old school Korean name.”

And for me, that was just one more thing that emphasized: it’s no accident that I have this affinity towards the Korean language and culture.

It definitely was meant to be. It’s incredible how both of your parents are somehow connecting the Korean and Black culture.

Right.

Supporting Other Adoptees

Related to that, I also wanted to ask how you came to hold Korean language classes for adoptees. I was looking at your website, and you mentioned how there’s a sense of shame for some of them if they have ancestry in Korea but don’t speak the language. What sort of discussions do you have with them? I’m sure there are straightforward language lessons, but do you also talk about identity?

Yes, absolutely. If we go back to the history of adoption, I was touching on the president who had the policy of sending mixed children to their father’s land, because a number of GIs who were white Americans or Black or other races came and had children with women. The president was essentially saying, “We need to keep our lineage pure.”

But then you also have children who are put up for adoption because both of their parents are Korean but they were born out of wedlock. Korea is historically very conservative. It’s been called the “hermit kingdom” because for so long it stopped outside influence. Even in the 1900s, there was a strong effort to preserve those customs. If anyone’s going to have a child, you have to get married first.

Or there were situations where a daughter might be put up for adoption because the family wanted a son. You have situations where children are taken without the parents’ knowledge and then put up for adoption.

That’s terrible.

Because the adoption system really became monetized, to the point that each child that’s put up becomes a good few thousand dollars that either the government or these private adoption agencies are making. They find a child that can be adopted and connect them with a host family in the United States. With these particular Korean adoptions, you don’t have to come and see the child first. Korea will prepare the child, put the baby on a plane, and then a representative from the agency will deliver them to your door. And so it became a type of business.

And now you have hundreds of thousands of these children, and a lot of them were sent to rural white towns. So they might grow up on a farm. No other family members look like them. No one in the community looks like them.

You grow up dealing with racism. You grow up and you’re always questioning yourself. You don’t know who your mother is. You don’t know who your father is. You’re always asking questions like, “Was I thrown away? Why was I thrown away?” And you start to question your own value, your self-esteem. You’re not confident in a lot of things because you don’t really feel grounded. And this isn’t every single situation, but there are many cases like this.

Then at some point, people grow up. And then they have a drive to find out more about their history, find their parents and see if they’re still alive, and learn about this Korean culture. So you have many cases where adoptees will learn Korean, maybe study somewhere in the States and then go to Korea, and try to do something as simple as maybe order coffee.

Now, if you imagine you’re in the middle of Korea, you’re ordering coffee, the person behind the counter is Korean. They’re born and raised there; they’re a native speaker. The adoptee is using what Korean that they can. They finally mustered up the bravery and the confidence to learn the language and actually use it.

And of course, as someone who’s not used to speaking and growing up [with the language], you’re going to have an accent, and your pronunciation is going to be a little bit off. So the person behind the counter sees a Korean person who is not able to speak Korean correctly. In certain situations, that brings a look on their face that’s almost judgmental. And that hurts. That hurts a lot.

I’ve heard of another situation where an adoptee entered a taxi, and once the cab driver picked up that they weren’t speaking correctly, they kicked them out. So you have a ton of people who have similar situations that bring them to a point where they’re no longer confident in speaking the language.

It’s almost like being stuck between a rock and a hard place because on the one hand, you have this burning desire to learn it because you know that’s where you come from. You know that that’s where you’re going to discover your roots. That’s where you’re going to find grounding in life.

But then you also know that you’re going to be judged or you have this lack of self-esteem that is so difficult to overcome because of a past negative experience with speaking.

So that’s where I found value in teaching Korean for people who are stuck in that cycle, to not just provide Korean language classes, but rekindle and grow that flame of confidence to speak fluently like they always wanted to.

It’s a membership organization, and I teach Korean classes. We also have different workshops and discussion groups around different topics. It can be related to speaking the Korean language or some past negative experiences, and how to put those in a correct perspective to help you move forward.

Or we might speak on other topics like family–different topics that people want to speak about but may not be able to bring up with their coworkers or adoptive family members. They want a community strictly of Korean adoptees who understand that situation, and will hear it and listen to it.

That is just incredible. I’ve heard from some Japanese American friends that when they go to Japan, their white friend or someone who doesn’t look Asian gets all the praise for speaking just a few words of Japanese. But if the Japanese American person or someone who looks Asian doesn’t speak Japanese, they’re immediately judged.

Yeah, it’s the same thing with Koreans, and that is a major reason why adoptees prefer not to study Korean alongside non-Koreans. It’s not racism. It’s because of those dynamics in the classroom.

The teacher would say to the Korean adoptee, “You need to speak better,” or “That was OK, but you should know better.” But for the Caucasian or Filipino or Black student, all they have to do is say hello. And the teacher will go, “My gosh, you speak so well!” and give them all these accolades and praises that the adoptee is also due but does not receive. It’s like, “I didn’t ask for this situation.”

The program that I have is called Speak with Seoul. And Seoul is spelled S-E-O-U-L, like the capital of Korea. It’s exclusive for adoptees or children of adoptees so that people don’t have to worry about those types of dynamics in the classroom.

That is amazing. I’m sure that it’s really a life-changing experience for them to be able to have this sense of community. And is it online?

Yes, online.

It’s great that they would be able to connect with each other from throughout the United States.

Yes, really throughout the world.

Everyone understands each other. There are a lot of things you just don’t have to explain. For someone with untrained ears, there are a lot of things you’ll have to explain, about the adoption story, or about why I feel like this, or why this or why that. But when people come, it’s an environment where it’s like, “Okay, I can just put all of that baggage down and be myself. Let me just learn Korean.”

Languages Deepen Mutual Understanding

That is wonderful. You’re also really active as an interpreter. Are you transitioning into Speak with Seoul, or do you want to continue interpreting while doing this on the side?

Both. I see both growing very large, and I expect to help a large amount of people with Speak with Seoul. And interpreting is one of the things where I find the most joy in my life and I think it feeds some aspect of my spirit, so I plan to continue to interpret as well.

Did you always have a love for languages while you were growing up?

Growing up, I had a love for diversity. Where we grew up in Seattle, our elementary school was very diverse. I remember our high school was probably 70% Asian. And that would be mostly Chinese and Vietnamese. There weren’t a lot of Koreans, if any.

And I remember seeing this a couple of years ago, but our zip code 98144, or one close to it, was one of the most diverse zip codes in the United States. In Seattle, you get immigrants from East Africa, Southeast Asia, South Asia, really all over.

A lot of my friends were Asian. I would go to their house and maybe see shrines or always hear their parents or their relatives speaking Khmer or other languages. And I always felt comfortable there.

When I entered high school, my uncle would take me on business trips with him outside the United States. So I visited Japan twice. I went to Korea for the first time with him. I’ve been to the Philippines. And every place I go, I always found excitement and joy in conversing with the people, but especially using their language. You relate with a person on a different level when you speak the same language.

Absolutely.

Body language and gestures will take you to a certain degree if you don’t speak the same language. But when you speak the same language, you understand each other on a much deeper level. And I truly enjoyed that growing up.

With your company, the Holloway Interpreting Group, you’re not only an interpreter yourself, but you also coordinate events by helping other freelance interpreters with assignments, right? What kind of things do you do?

A mix. I try to share or utilize basically anything that I know. With the Holloway Interpreting Group, I present regularly for other interpreters, whether at different interpretation conferences or my own webinars. I also have a monthly newsletter that touches on different aspects of interpretation. And a lot of times, people are just interested in hearing my life story. So in the monthly newsletter, when I put like a blog post in there, I’ll talk about different things, not just interpreting. And I’ve trained interpreters in the past and can do that as well.

Building Confidence

That’s great. In one of your latest newsletters, you talk about how interpreters should exude confidence. Every time I speak with you, you seem like someone who’s so put together and confident in your mannerisms, voice, the way you present and whatnot. Did you always have that confidence growing up, or is that something that you acquired as you gained more experience?

Both yes and no. But I don’t know if my ambition just looks like confidence. I’ve always had the drive to pursue certain things. But from time to time, people have told me, “You need to be more confident.”

One of my first simultaneous interpretation experiences was a remote simultaneous interpretation (RSI) assignment. It was a four-day webinar where I was working with a veteran Korean conference interpreter.

Anytime I work with veterans in the booth, I always pick their brain and ask at the end, “How can I speak better or be a better interpreter?” especially because Korean is my second language.

So at the end, I ask, and I’m expecting an answer that is along the lines of, “You need to increase your vocabulary,” or “You need to become more adept at these types of sentences,” and so on and so forth. And she’s like, “You don’t sound confident on the mic. You need to sound more confident.”

Really!

And I didn’t see it myself. So her comment really blew me back. And that was it. She was like, “You just need to work on that.” I’m like, “Okay, if you say so.”

So shortly after, I practice interpreting and I record myself. And then I listened back to the recording. And it’s just riddled with, “uhh,” “yeah,” “but,” “and um”–all these fillers. And it just sounds disgusting.

No way!

And I’m like, my gosh, this is what she heard. I get it now. That was golden advice, actually.

And from that point on, I decided I will not sound like that ever again on the microphone. And that’s when I started getting rid of fillers. I’m okay with silence for a second.

That’s when I started in other ways to improve my voice. A lot of it was listening to other people whose voice I admired and then mimicking that.

That is something that I really wanted to hear personally because with this podcast, I’m also struggling. Just being on video makes me so nervous! I think I’m slowly getting better, but yeah, the filler words are so hard.

Sometimes you have to partner with or work with people who are basically native speakers of that language. Did you ever struggle with that?

It can be intimidating. I wrote a book recently called Interpreters, Translators, and Confidence, and in that book I touch on this. I acknowledge my weak points, and I work on them, and I acknowledge my strong points.

That’s one of the reasons why, after working with a veteran in the booth, I always ask. I force myself to have the humility to ask. I’m in a situation constantly where, whoever my partner is, their first language is Korean. I just personally don’t know and have never worked with other conference interpreters who have Korean as their second language.

So I always take it as an opportunity to learn from the other person more than anything. And then when I need to acknowledge my weakness, I do that. And that rule or principle has helped me until this point.

There have been a lot of situations where I have felt imposter syndrome. Even so, I don’t allow that to hinder my capability or confidence. I really work hard to push those thoughts out of my mind.

You can know that your partner is better than you. But you just have to put it in a good perspective. If this person is better than you, instead of having imposter syndrome, you have the perspective, “Okay, I’m going to learn from this person. I’m going to pick your brain. As you’re interpreting, I’m writing down your sentence. I like that word that you use. I like those sentences that you use. I’m copying you and that’s going to help me become better.” And you just put your focus there.

You can fill your brain with any thought. I choose not to fill the brain with negative thoughts when I’m interpreting.

That’s really inspiring. And that’s something that can apply to all sorts of things that we do in our life, and even just how we live: think positively and continue to learn from others.

Absolutely.

Culture as a Foothold for the Future

Last question: would you have any advice for people who might be struggling with their identity or trying to fit into a community?

Well, it’s a very broad question, but what helped me was exploring my own culture. And the importance of culture is that, every human being at some point in their life comes to the question of “Why am I here? What’s my purpose? What is my identity?” And that’s not just 2024. For hundreds, thousands of years, human beings have been asking that.

The value of a culture is that people have come together in communities, and based on where they are in nature, based on where they are in life, have defined themselves the best that they possibly can. And they took those principles and values and passed it down to their children, so that every next generation that comes has a strong foothold. From that foothold with your culture, you know the foods to eat, you know how to heal yourself, you know about the clothes that you wear, you know the names of your ancestors and so on and so forth.

Some people will stay within that culture very tightly. And some people will use that as a basis and then explore more, learn, and go see other aspects of the world. But your culture provides a foothold. That’s what it’s done for me. And once you have that foothold and once you know that’s right in your life, that gives you the confidence to go do whatever else that you desire to do.

This is fascinating. When I ask this question to other guests, a lot of their advice has been about how to live your own life. This is the first time I’m hearing an answer that really goes into the history of it all. And I think it might be reflective of the history that we just talked about, your family ancestry, and looking into your grandparents and whatnot. So thank you very much. I’m learning a lot.

Yeah, absolutely. We’re not the first ones born on earth. We’re coming into something that’s already operating; we didn’t come and then create the trees, for example. Culture is the same thing, but once you discover your culture, you find that you learn more. That’s when you can say, “This belongs to me.”

You can eat sashimi, for example, and feel within your being, “This is mine, this belongs to me, this is what my people do.” Once you have that firm grounding within yourself, then that gives you the tool to be able to go anywhere in life.

That’s true. Well, thank you so much for that.

I think we went over all the questions that I wanted to ask, but is there anything that I missed or anything you’d like to add?

No, I just want to say thank you for having me. And if you want me on again, I’d be more than happy to come back on the podcast.

Thank you!