Originally from Tokyo and now based in Seattle, Yuko Watanabe is a strategy & operations consultant who is passionate about innovative technology that tackles the world’s big problems. She has an MPA from Harvard, along with 13+ years of cross-industry experience serving big tech, startups, government agencies, and nonprofits worldwide, such as Google, Starbucks, Microsoft, the Gates Foundation, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), and the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC). She enjoys working creatively across the traditional boundaries of corporate, government, and nonprofit sectors, and is proud of the cross-country initiatives and communities that she has built so far. Yuko also teaches Ashtanga vinyasa yoga at The Yoga Shala Seattle and hosts the writing & self-reflection online communities Tapestory and All our tomorrows.

(Click on these icons to follow Yuko: ![]()

![]()

![]() )

)

Podcast

Transcript

Introduction

Hello, everyone. I’m excited today to welcome Ms. Yuko Watanabe, who was born and raised in Japan and now lives in the United States. I’m in awe of her initiative to build communities, especially those online, as well as her warmth, her great sense of humor—which I’m sure will come through today’s interview—and her ability to tackle anything that comes her way. Thank you so much, Yuko, for joining me today.

Thanks for having me.

Childhood and Upbringing

Without further ado, I wanted to ask you where you were born and raised.

I was born and raised in Ota-ku in Tokyo. Ota-ku has two parts, the nice part and the not-so-nice part. And I was born in the not-so-nice part near Haneda Airport. It’s an industrial area. I was born in the mid-80s, and back then there were lots of little factories.

I remember that in the summer, a siren would go off at 3 p.m. every day and say, “Hey, the air pollution is so bad that you have to go home.” We can’t stay and play outside. We have to go home. It’s that industrial. That’s the little neighborhood that I grew up in.

To paint the picture a little bit more, it’s like a massive danchi [Japanese multistory mass housing that was popular in the 1960s and 70s]-style apartment. My dad moved there when he came to Tokyo from the countryside to go to college, and my parents still live there. I grew up in this small studio apartment, and I never had my own room.

So you lived in an area where it seems you didn’t have a lot of daily interaction with people from other countries. How did you end up being interested in living and studying abroad? Could you tell me about your trajectory from then until now?

I went to a local public elementary school and middle school. And in an industrial, not-so-nice area, as you can imagine, the school was full of kids with lots of trouble. I think their parents were running these factories. They probably had a lot of financial hardship.

My memory from middle school is coloring in my science class, like maybe chemistry or biology. I remember coloring [illustrations of molecules] for like the entire 60 minutes: “This is H2O. Let’s color H red, and let’s color O blue.” Because that was the only way the teacher could engage the kids for the whole 60 minutes. During my last year in middle school, that’s what my science education was. And I was like, “Oh my gosh, this is crazy.”

But I luckily had a neighborhood juku [cram school], where I went after school to study. I did really well there. They had fantastic teachers and great classes, and I really enjoyed learning math. I’m still in touch with my math teacher.

I really enjoyed studying and learning things outside of school. So I studied really hard and got into this fancy high school that was like an hour and a half away from my neighborhood in the middle of Tokyo.

When I got to that high school, that was when I realized that there were kids who lived or studied abroad, or had parents who speak English. That was the first time I realized, “Oh, there are people my age who actually speak this language?!” Up until then, all I knew about English was the sentence “I have a pen.” That’s all that I learned from textbooks. I didn’t really think that people actually spoke it.

I don’t think my parents listen to foreign music or watch foreign movies or anything international. So I didn’t really think it was an actual living language. It was really shocking when I went to high school and found that my friends and classmates could actually speak English. I thought, “This is it. I want to learn this thing that they’re speaking. I want to learn to speak English.”

I looked into summer study abroad programs. Turns out, they were too expensive. I couldn’t afford them. So I thought, “Okay, I’m giving up. I can’t do this.” This is the summer of my first year in high school.

But at the very end of that summer, my mom went to this local neighborhood shopping mall and she got a ticket to draw a fukubiki. I don’t know how you say that in English, but it’s a raffle, with a big red machine [that’s rotated] like Bingo, and a ball comes out.

She only had one ticket so she rolled once. And then there comes a golden ball, and everybody went, “Ding ding ding ding ding ding ding, first prize!” My mom won a ticket for two to go to Sydney, Australia for a week. I was like, “This is it! I can finally go outside Japan for free.” I was 15, in my first year of high school.

I went to Sydney for a week with my mom. That was the first time I got on an airplane, the first time I got a passport, the first time I packed a suitcase. It was very exciting. I still remember things from Australia. I really loved that experience.

[Afterwards,] I kept doing the same thing and couldn’t win the prize again. So I applied to study abroad programs that were funded by MOFA [the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs]. It wasn’t completely free, but almost free. I kept applying to these programs the next summer during my second year in high school. In my last year of high school, I enrolled in another study abroad program, and I kept going. That was my introduction to the world outside Japan.

Studying and Working in International Development

Amazing! Am I correct that in one of those trips, you went to China and the Philippines and became interested in international development?

Right. I wished to go to a country where people spoke English. My initial intent was to learn English. But the study abroad programs to English-speaking countries were pretty pricey.

The only free one that I could find was to this small city in Northern China called Mudanjiang. It’s very north, closer to Russia than anything else. It was small back then, but I’m sure it’s different now. I loved being in that town. Everybody was so nice. I made so many friends in my class. But no one spoke English. I learned Chinese instead, which was fabulous!

And then a year after, I found the Philippines in the brochure and thought, “Okay, they must speak English.” I did learn a little bit of English. People did speak English, but also mostly Tagalog, so I learned that too. But you know, baby steps.

It wasn’t really my intention, but I ended up going to these countries and got really interested in why I saw people and children my age begging on the street. Back then in China, in the apartments where my host families were living, they had no running hot water or lights in the apartment. I thought, “We are right next to Japan. What is going on with this economy?” That’s how I got interested in studying international development, or just economics in general.

So you went to the University of Oregon to study it, then?

That wasn’t really my first choice, either. Now that I think back, Oregon’s fantastic. I’m not saying anything bad about Oregon here. I decided I wanted to study International Development Economics. I’d never been to the U.S., but I was determined to study that and get a master’s degree in the U.S.

I figured it’s easier to get my undergraduate degree in the U.S. as well, rather than doing it in Japan and going over. I figured like I might as well just go straight to college in the U.S. But then at that point, I had zero [contacts]. I didn’t know anyone in the U.S., and I’d never been there. The closest place abroad I’d been to speak English was Manila.

I had no connections. I had no one to ask any questions. I had no idea. I saw this flyer in my high school. There was an agency that can help students go to colleges in the U.S. I’m like, “Okay, I’m going to apply to this. I’ll pay a little bit of money to this agency and see where I end up.”

That agency listed all the colleges in the U.S., but I thought, “My parents are in Japan. So let’s go to the West Coast because it’s closer to Japan. And let’s not go to California because I heard there are lots of Japanese speaking people. I might not learn English.” Then I looked at the map and thought, “Washington seems really north. It must be really cold. Let’s go to Oregon.” So I went to the biggest college in the state, which is the University of Oregon.

And I love Eugene, Oregon. It’s cute. Now I really love it. But back then, gosh, it was so very shocking. All I could see were these beautiful mountains. And as a person who’s born and raised in Tokyo, I was like, “My gosh, all I can see are these mountains! Why did I come?”

So that’s how I ended up in Oregon. I didn’t love it then. I absolutely hated it. I thought it was the sleepiest town ever. Nothing was open except for the library and Starbucks. Nothing was open after 10 p.m. That’s what I remember, because I probably didn’t know all the fun places. So I studied really hard—way too much. And I graduated in a little less than three years.

Amazing! Wow!

Just because I wanted to get out.

No, you’re too humble! That’s a lot of hard work.

After that, I understand you worked in international development at some organizations. Would you mind talking a little bit about that?

I studied really hard in Oregon, and made sure I got really good grades so I could go to a good grad school. And when I got to my grad school, I did a couple of internships to see, “Do I really like this career? Do I really like this field of international development?”

So I got an internship in Bangladesh working with the United Nations. That was like my dream come true. That is exactly what I wanted to do ever since I’d been to China and Manila.

And I didn’t like that experience at all. It was really hard for me. And I realized, this might not be the kind of thing that I want to do. There’s a lot of politics. It was a difficult time for Bangladesh then. A lot of things and changes were happening within the United Nations and the agency I was in, and that was a little too much.

I thought, “Maybe I should go back home and work in a Japanese agency that works in international development.” So that’s exactly what I did. After finishing my grad school in the U.S., I went back home and worked for a couple of Japanese government agencies that did international development.

It was a very interesting experience. After spending several years in the U.S., now I’d become somebody not 100 % Japanese. I found it really hard to fit in the way of doing things in the Japanese government. I can’t generalize it. It’s really different from team to team, I’m sure. But I had a really hard time fitting in. And that’s how I came back to the U.S.

Living on the West Coast

What do you enjoy most about American culture? You said that you’ve always wanted to study English, but it seems like you’ve been drawn mostly the U.S. For example, you went to Sydney first, but you didn’t go to Australia after that to study abroad.

I think I chose the U.S. mostly because, to have a career in international development, I knew I had to get a master’s from well-known colleges, and those are mostly in the U.S. That’s what my first thought.

And after living here for a while, especially on the West Coast, like Oregon, I found that people are just so nice. They’re very chatty. If you’ve been to a supermarket in Oregon, people would just chat and chat, and in a similar way, you go to Trader Joe’s and people start talking about like, “How do you cook this?” And that happens everywhere. It’s just so casual and nice and friendly, and that’s something I really enjoyed.

It’s closer to how I grew up and what I’m used to. Again, I didn’t come from a fancy, well-established family in Japan. More broken style, casual, and everybody’s friendly. So I enjoy this—I don’t know if I should call it West Coast culture—sort of casual frankness in the U.S. Everybody is equal. Everybody’s friendly. That’s despite the fact that I really didn’t enjoy Oregon the first time I was there. I think that really changed who I am very early on in my life. Now I’m like, “Okay, this is nice.”

Going Freelance

I wanted to ask about your current work. I understand that you went freelance a few years ago. It must’ve been hard to let go of all these prestigious organizations that you worked at, because it was your dream for such a long time and you had gone to grad school for it, etc. It must have taken some courage to go at it alone. Would you mind explaining that decision?

Sure. I wish I could glorify it and say that it was by choice, but it wasn’t. I was laid off. And going freelance was pretty much the only choice I had. I had a newborn then, and it was maybe my third year living and working in the U.S., where I didn’t have that many friends. I didn’t have family. I had pretty much no support.

I had to find a job. Up until then, most of my experience had been something to do with U.S.-Japan relations. And being based in Seattle, there’s not that much work in U.S.-Japan relations. There might be some, but I found it really difficult.

The only choice where I could continue having a career was going freelance and taking up small projects to make it a full-time job. So it wasn’t really by choice, but that was my way of trying to figure out my career: “What do I want to do? What can I do? Or what do I want to do when I grow up?” I was still trying to figure it out. I still don’t know if I figured that out now, but that was an interesting period of my life, going freelance and figuring out, “What do people think of me? What do people think I’m really good at, versus what do I want to do? Where does that overlap?”

And what kind of work do you do? Is it mostly consulting?

Mostly consulting, and a variety of things. I did everything. I did things like translating documents or reports between English and Japanese, and translating marketing websites that some small startup ran. [The work was] sometimes U.S.-based, sometimes Japan-based. And then everything in between. I also did some things related to international development. I did some things that have nothing to do with international development, but more to do with the local startup scene in Seattle, some product that they wanted to sell to people in Japan. So a wide spectrum, all sorts of work—I tried everything. At the time I thought, “I’m going to do everything I can and see what sticks.”

Family Life

I love that initiative you have. You mentioned that you had a newborn that you had to take care of. Just to backtrack a bit, would you mind explaining about your family, like how you met your husband, where you are now with them, etc.?

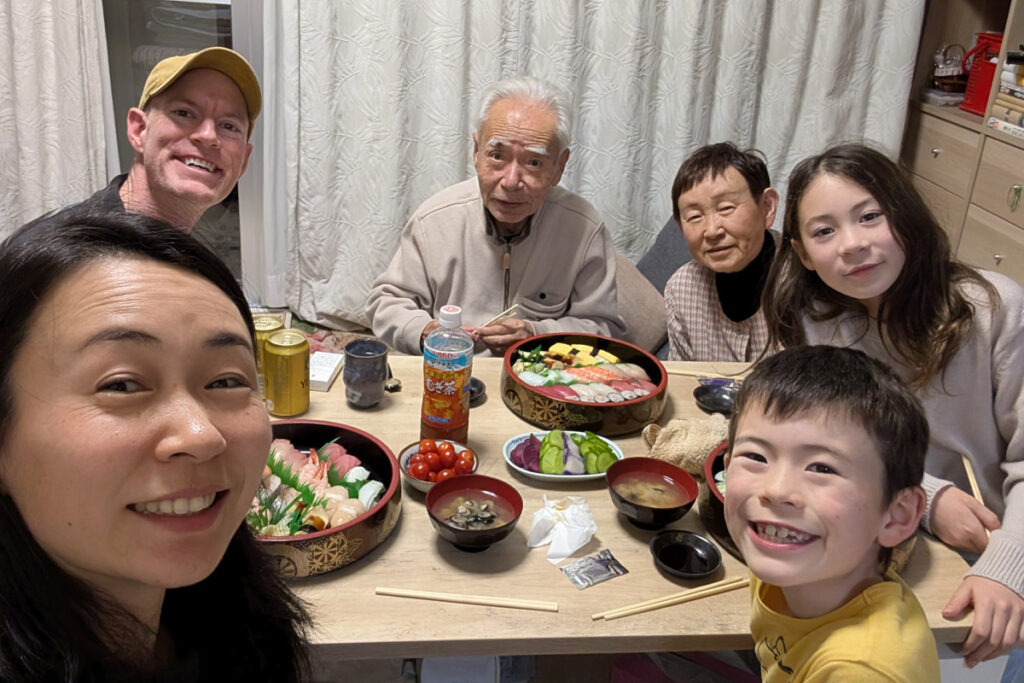

I met my husband in my grad school program. He also worked in international development. And my parents are still in Tokyo, but his parents are on the East Coast in the U.S.

When I realized I was expecting, we were living in Japan. We wondered, “We’re starting a family. Do we want to continue to be in Tokyo, both working in international development?” That meant me taking international flights, mostly over 24 hours. I was flying to Ethiopia quite often then. He also had a project in Rwanda and Kenya. So he also had a lot of flights going out. We hardly saw each other in Tokyo, and looking ahead with a baby coming, we said, “Okay, maybe this isn’t sustainable.”

We looked at the world map and said, “Where do we want to start a family together?” And we said, “Eh, maybe Seattle.” Despite the fact that we’d never been there, we had no friends, we had no family, and we didn’t know anyone.

My husband, Nick, flew here first, looked for a job, and luckily ended up with one. So I thought, “Okay, he has a job, he’s got health insurance, so let’s have the baby in Japan and then fly over.” So I came to Seattle almost 11 years ago with a six week old baby in my arms. And that was my first day in Seattle. And I got a job locally here.

It was when I had the second child that I was laid off. So when I went freelancing, I had one kid in daycare and another who was just an infant.

Wow. I had no idea you hadn’t even been to Seattle. Do you think you’ll stay there going forward or do you have any future plans?

We’ve been here for 11 years and the biggest reason we really like it is the schools. In our neighborhood, we have two public elementary schools that do immersion Japanese education. So my kids go to this local school. Half of the day they speak in Japanese. Their teacher’s Japanese. They learn science, math, and language from this Japanese teacher and do all these cultural celebrations like Hinamatsuri [Girls’ Day] and Obon [a holiday commemorating ancestors and loved ones who passed away], which I really appreciate. It’s a wonderful school and the kids love it too. So I think we’re going to stay here.

But my years in Japan and the U.S. is becoming kind of equal. And we’ve started to think, “Do we want to stay here? Do we want to go back to Japan? Or do we want to go somewhere else?” So we’ll actively think about it. Maybe in the future, we might go to Japan again or somewhere else in the U.S.

Loneliness in Perspective

Thank you so much. Earlier, you mentioned that after studying and working in the U.S., you decided to work in Japan and felt like you weren’t 100 % Japanese anymore. I assume your identity is constantly changing. I was wondering if you ever feel a sense of loneliness sometimes. Here in the United States, maybe you feel like your Japanese identity is strong, but when you’re in Japan, maybe not so much. How do you grapple with that loneliness?

It’s interesting that you ask. I don’t think I’ve felt that lonely in Japan or in the U.S., mostly because I’ve spent so much time outside of these two countries and realized what loneliness really is like. I spent almost a year in a remote village in India. There really was no one who wasn’t from that town. I was the only one. It’s tough to have no friends, no family. You might have colleagues. But that’s really, really tough.

So in a relative sense, I’m happier and having an easier time finding friends and people to connect with in the U.S. or in Japan. For example, in Seattle, there’s a big community of Japanese American people. I never feel like I need to actively seek friends. There’s a lot of people to connect with and it’s relatively easy. People appreciate Japanese heritage. And also, in Japan, it depends on which sector you are in, and what kind of work you do, but I think it’s easier to find people. I think it’s harder when you’re outside of these two countries.

That makes sense. Speaking of which, how did you live your daily life in a remote village when you might not speak the native language and there weren’t many others who look like you or were like you?

I think if I did that today, it would look very different. You have access to the internet, you have phones. Back then, I wrote letters, read books, and called people with an international phone card. There was nothing that I could use to immediately connect with people. So it was very difficult. It was very lonely. I read a lot of books. I wrote a lot—letters to friends, journals for myself. Maybe that’s one of the reasons why I still like reading and writing.

Online Communities Based on Writing

Thank so much. I think that’s a great segue into the next question I wanted to ask. I really love the online communities you’ve been making based on writing, first with All Our Tomorrows and then Tapestory. Could you explain what you ask people to do and why you created that community?

All Our Tomorrows is a blog site that I’ve been running for more than maybe 15 years now, with lots of essays from others about what they’re struggling with or whatever they want to write about.

[The writers are anonymous, and] all they say is their age, and whatever title they want to give themselves, which mostly turns out to be their profession. I give them no themes or instructions, no deadlines of any sort, no structure. It’s very free form. I wrote one piece first and asked my friend to write another one. It kind of went on. So I have almost a hundred essays on that website written by women around the world, mostly of Japanese heritage.

That kind of transformed into this thing called Tapestory, which started during the pandemic. I paired with my partner Kei-san. She is a coach, and she can help people think about the struggles and challenges that they want to talk or write about. So it’s a little easier for people to write. Until then, I was just asking people to write. But as you get older, there are more things to unravel. And she was very helpful unraveling those things internally so that people felt more ready to write. Tapestory has several essays too, all similar in style about what they’re thinking about in their career, their life, all sort of things.

It’s so interesting how you ask them to write their age and then, as you said, profession or however they call themselves. Why do you make it anonymous? And why is age important in this case?

That’s a good question. I started it when I was living in Tokyo but commuting to Ethiopia. I had a friend who worked in Ethiopia, and I could tell she was feeling very lonely. Her friends and family were far away, and I could totally understand how she felt based on what I went through in India.

She couldn’t have one-on-one conversations with people. There was no Zoom back then, right? All you can do is exchange letters. So I thought, “I’ll have one-on-one conversations on behalf of her in Tokyo, write up these pieces, and then post it so that she can read it and feel like she talked with these people.” Now, I didn’t do my work; I just let other people write those things for me. But essentially that’s how it started.

And at that point, age felt very important, because we were often writing about, “I like this boyfriend,” or “We’re getting married,” or “We’re expecting a baby,” or a lot of life and career choices that are age-sensitive. Now I think it’s also a very interesting thing to have too, just to imagine who is writing this piece at that age and what they do. And that’s really pretty much the only clue you have to who the author is.

Friends with the Same Name

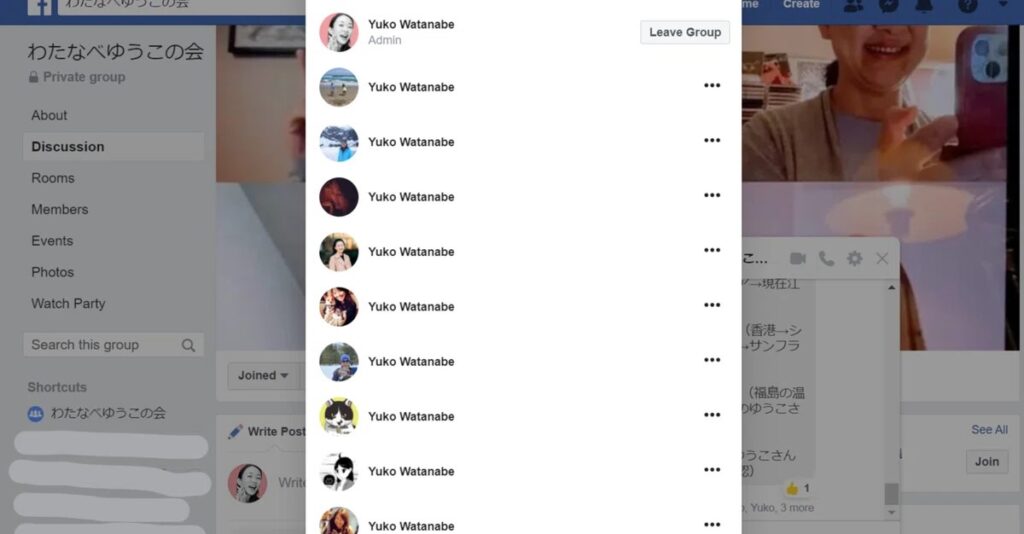

That’s fascinating. Related to that, I want to ask about another amazing community you have. In that case, everyone does have a name—but it’s actually more difficult because everyone has the same name. Could you tell me about the Yuko Watanabe Club [where all members have the name “Yuko Watanabe”]? Are you one of the founders, and what do you do?

I’m one of the early members. I’m number three, I think. And I think we have close to 60 Yuko Watanabes in the club right now.

What!

But we’re nothing compared to Tanaka Hirokazu. Because they found over 200 Tanaka Hirokazus. A couple years ago, they got together in Shibuya, like all 160 of them [who were members at the time]. They applied for the Guinness World Record and they were awarded, only to be beaten by someone else in some other country.

Wow. That’s so cool!

You should read about it. It’s fantastic. They’ve started a company, and they have all these gifts and products and t-shirts you can purchase. It is very cool.

If you’re in this club, you feel this instant connection with these other Yuko Watanabes. It feels like you’re friends with them. And I’m also one of the biggest victims of having the same name, because I have a very standard email address. All the emails come to me, so I get a glimpse into the lives of various Yukos. She went to the dentist, she had this order this water thing or this cosmetic. She didn’t go to the dentist again. So I often just text the Yuko Watanabe group and say, “Who was it that was invited to this fancy party in Shinjuku?”

That’s hilarious! So how do you address each other?

We follow the same norm as the Tanaka Hirokazu group, where they add locations like “Tanaka Hirokazu of Shibuya” or “Tanaka Hirokazu of Seattle.” So I’m the Yuko Watanabe in Seattle, and there’s another Yuko Watanabe in Shibuya. Or maybe there’s the writer Yuko Watanabe. There are different ways, and you kind of choose whatever you want to be called.

And everyone has a number. I’m number three. There’s a big spreadsheet that we can look up. It’s hilarious. We’re trying to make this a fun thing.

But most of the time, having the same name is not fun. I work as a consultant. There’s almost always another Yuko Watanabe in the client company.

I also get in trouble because a lot of emails don’t come to me. They’re sent to the wrong person. For example, when I got admitted to my grad school, I got the admission letter, but I didn’t get the emails afterwards because they were going to the other Yuko Watanabe who was in the same program two years before me. I thought maybe somebody was pulling a prank on me, and I wasn’t actually admitted! But apparently I was, and I’m glad. There are so many things like that.

So we’re trying to make it more fun so that it’s good to be in the big group of Yuko Watanabes. Eventually this can become like a benefit. You get 20% off if you go to this Yuko Watanabe store. You get this membership if you go to this store, or something like that. That’s our goal.

I’m sure that so many of you have struggled with this your entire life, but then you have this really fun way to turn it on its head and have so many interesting perspectives. And I think that’s a really wonderful way to connect with each other.

This is true for Tapestory and All Our Tomorrows as well, but as you get older, it becomes harder to make friends with random people. There’s no school that you can go to. You don’t switch your jobs that often. So it’s kind of a fun way to meet complete strangers and become instant friends.

Staying Nimble

Right. Thank you so much. What are your future plans? It could be for these projects that you’re working on or it could be for work. Do you have any dreams and goals that you want to share?

Nope. I have no idea. Please—you tell me!

I love it!

I used to think that there are goals, resolutions, paths, and careers. Nah. I’ve given up. There are so many things at this point in my life: the kids, my husband, my job, my kids’ education, my kids’ sports, my parents’ health—all sorts of things. It’s kind of out of my hand.

So the best I can do is to stay well and be ready to move in whatever direction I need to move tomorrow. That’s the best I can do. I stopped making long-term plans.

Okay. You also mentioned the possibility that you might move to be closer to your parents in Japan at some point. Is that something you’ll continue considering as well?

Yeah, I’m an only child, and my parents are over 80 years old. So I’m thinking at some point in my life, I will have to either commute to Tokyo to take care of them pretty often or move closer to them. We’ll see what happens.

That’s one of the big reasons why I need to be nimble. I need to remain nimble and be ready for anything that comes up in my life. And I’m okay with that. It’s not like you get a job at this fancy company and your life is done. No, you get laid off. You don’t know what’s going to happen. So you might as well be ready for anything.

That is an amazing and wonderful perspective. And that’s something that I needed to hear, because I tend to really wonder and worry about my future. And I’m an only child as well and think about family a lot. So it’s really nice to have someone who’s on the same boat. There are actually many of us.

Find Joy in the Struggle

Would you have any advice for anyone else who’s struggling with difficult life choices because they might be living or working in multiple countries?

It’s a really hard question. But I think I’d say, get used to that difficulty because it’s always going to be a struggle. Find joy in that struggle, because it’s going to go on.

And I’m going to talk about yoga because this is how my brain works. I do yoga every morning. In the style of yoga that I do, early on in the series, there’s one pose. You stand on one foot, take the other foot and move around, and bend forward and then balance. It’s a really difficult pose because you’re standing on one foot and balancing.

I always thought, “If you practice this pose every day for many years, you eventually get to this perfect balance. You don’t fall, you look amazing, you feel amazing, and you’re amazing. The rest of the day would be amazing.”

And I started to realize, no, there’s no such thing. We’re not a robot. No matter how many days or how long you’ve practiced this pose, you always fall out of balance. The best thing you can do is stay well so that you find ease in that really difficult pose. That’s the best we can hope for.

And I feel like life is similar to that. Balance is not something you reach, but you’re always working towards it every single day. And that perfect balance point is different every day. So you kind of have to work hard to find that balance. That’s every day, and that’s life. You have to find joy and ease while struggling.

I feel like that’s my life as well. There’s no perfect combination of identity or language mix or cultural affiliations or job or whatever. There’s no such thing. And what I feel comfortable with today might be very different from what feels comfortable next year.

I remember at the beginning of the pandemic, I was freaking out that my children were speaking more English and less Japanese. Now I’m completely comfortable that they’re totally speaking in English. Things change and it might change again as well. Maybe in five years they’ll be speaking in Japanese. Who knows? But I’m okay.

I hope that made sense.

Absolutely. And I’m really glad you brought up yoga. I was meaning to ask about it. I think it’s so incredible how everything you put your mind to, you work so hard at it and go all the way to the top. I was really surprised to learn that you only started yoga just a few years ago and now you’re a yoga instructor. That’s incredible.

I think that really covered everything I wanted to ask, but is there anything you’d like to add?

No, but I really wanted to thank you for doing this. I think your intention here is very similar to how I started All Our Tomorrows, except that it’s really hard to take these conversations public. That’s why I started asking people to write their own pieces. But I don’t have to do very much. Here, you have to edit, write, take it on the website and do so much work.

I’ve had these one-on-one conversations with friends and mentors, neighbors, anyone, a lot of people at like all points of transition and all over the place. And those conversations really shaped me today. So I think what you’re doing here is really important. And I think you’re giving hope to a lot of people around you too. So thank you so much for doing this.

Thank you. Like you said for your essays too, none of this would be possible without everybody contributing their stories and really opening up. Thank you so much.

And as I said in the beginning, your sense of humor is amazing. I laughed so much. And I already feel better because of that too. Just having a sense of humor about everything and being flexible and taking things as is, is something that I’m really learning from you. So thank you so much for that.

Thank you so much for having me.