David Caprara is an award-winning multimedia journalist based in Japan. His documentary work has ranged from covering Nepali honey hunters in Himalayan foothills, to reconstruction efforts after the 2011 Tohoku disaster, to uncovering the mysteries of a WWII B-29 crash on a Buddhist holy mountain. He first came to live in Nara in 2012 as a teacher for the JET Programme. After spending several years freelancing in various countries and reporting for NHK and the Tokyo Shimbun in New York, he moved back to Japan in 2019. He lives in a kominka that he bought in the same Yoshino region of Nara where he was teaching as a JET and has enjoyed the world of discovery and friendships that the kominka community in Japan has opened up to him. In addition to his media work, David is a Shugendo Buddhist monk of the UNESCO World Heritage-recognized Kinpusenji Temple.

(Click on these icons to follow David: ![]()

![]() ; website: www.davidcaprara.com)

; website: www.davidcaprara.com)

Podcast

Transcript

Introduction

Hello, everyone. I’m excited to welcome today David Caprara. He’s a journalist who’s based in Japan, in Nara Prefecture. We met through the U.S.-Japan Council. I am just in awe of his work because he’s based in Japan and completely bilingual, but also working for major corporations in the U.S. And he’s had a lot of amazing stories, which I’m excited to hear about. He’s also worked in Nepal, Korea, and other exciting places. Thank you so much, David, for joining me today.

Thank you, Shiori. Good to see you again.

Childhood and Upbringing

Could we start by talking about where you were born and raised?

I was born and raised in the U.S., in the state of Virginia. Through my life, I’ve had a sample of many different sides and parts of Virginia. I was born in Fairfax and spent the first chunk of my life in Alexandria (both of my parents were working in DC), but most of my life in Virginia was in Fredericksburg.

In terms of cross-world connections, Fredericksburg has this swirling of cultures in the U.S. where the North meets the South. That’s true both historically and currently, with a lot of things going on in Virginia.

I had a lot of international friends growing up, but in my neighborhood in Fredericksburg, there weren’t too many people with an international background in the public school system. Two of my best friends there were also named David, and all of our dads were David. It was very confusing. So I started with the Japanese style very early, where we referred to each other by our last names.

One of them was adopted and had Korean roots. His grandmother was living in that house, which was within walking distance of mine. She was actually a Japanese woman who came there after the war. And just out of coincidence or goen1, her father was the guji, or shrine priest, of Kashihara Jingu in Nara, where I’m currently living, and then went on to be the shrine priest of Hanazono Jinja2. So I got early understandings of some Japanese culture from her. And seeing the way that my friend practiced these different traditions and cultures gave me an early introduction to Japan.

I also did a lot of travel, starting from middle school and high school. I made some international trips and had my first experience of going to another country that was different from what I knew and grew up in. I remember going to Korea for the first time and having this drink that had whole grapes in it. And I went back and told my friends, “In Korea, they have these drinks with whole grapes, and the floors are heated! And in Japan, they have convenience store ice cream that are unbelievable!”

These were early, simple discoveries, where I was seeing how things were different. They were kind of superficial, talking about ice cream and sweets as a kid. But maybe this was the early beginnings of trying to visit a different place, like bringing little snowballs back from the Himalayas or the North Pole, and sharing with other people what life is like in other places.

Experience on the JET Program

You said that you were already interested in Japan and Korea from that early age, but when did you start learning Japanese? Was it with the JET (Japan Exchange & Teaching) Program that you went on, or did you study it in school as well?

I studied French. I started in middle school and studied it through high school because it was one of the only languages available. Then I got to university, and with the momentum of already having that, I continued with French. And now I don’t use it at all. I studied Arabic as well. I also don’t really use that on a day-to-day basis.

So yeah, Japanese for me began with the JET program. Through university, I got interested in different cultures throughout Asia, and in meditation. One of my majors as an undergraduate was Religious Studies. I studied different forms of Buddhism throughout Asia. The University of Virginia [my alma mater] is very Tibet heavy. The Japan program was not very strong at the time. But the professor of one of the classes I took there recommended the JET program. He said, “It’s a great way to dig in and get a really deep dive into Japan.”

After university, I found myself Googling jobs and searching LinkedIn. And I thought, “This isn’t really a way to start a life.” So I got a backpack and backpacked around Nepal. I was thinking of just going for two weeks, but I stayed for five months, which was the maximum on a tourist visa. I just had a really incredible experience there. And I applied for JET while I was in Nepal.

On the JET Program, I was placed in a little town called Kawakami in Nara Prefecture, not far from where I am now. It was a very interesting region. Nara has so much history. Anywhere you go, just every inch of Nara, there’s hundreds of years of history to be told. But Kawakami is very remote and very extreme in terms of rural depopulation and the view that you get of Japan. It’s almost like a different country compared to Tokyo and what you’d see there. And I’m so thankful for being placed there.

While in Japan, a lot of the JETs [JET program participants]—and some former JETs listening might remember this—hear over and over again that every situation is different and depends on you’re placed. Initially, a lot of the people placed in very rural areas would look at people placed in cities and feel that they’re missing out on all the fun. But it was actually quite the opposite. It was in the countryside that JETs really had this strong sense of community. We would hang out all the time.

And the Japanese culture that I was exposed to in Kawakami and this rural area of Nara really let me see sides of Japan that are endangered—in terms of questioning how long this can continue on for—but also very uniquely Japanese. People were proud to continue traditions that have been going on for so long. So it was just amazing being able to form relationships with these neighbors.

I started with taiko3. I didn’t really speak any Japanese at the time, but someone told me, “You should get involved with this taiko team.” And it was through taiko drumming—music being a nonverbal language where you can convey more than in any language that you’re fluent in—that I saw these different sides of what it means to be a human being. Our taiko team had so much passion. I’m still connected to these people today, and they became like family. If it wasn’t for that early experience in taiko, I probably never would have had the sense of belonging and sense of family that I found here in Japan.

Building a Career in Journalism

I also wanted to ask you about your interest in journalism. It sounds like you’ve always been interested in history and in exploring cultures and whatnot. What led you to your interest in capturing and conveying that to others through writing, photography, or documentaries?

I’m in the millennial generation, where we didn’t have smartphones growing up. In high school, I had this point-and-shoot camera. For me, it was an artform to capture the daily things in life and the beauty of the mundane. It was also this meditative practice of taking a moment to slow down. There’s this idea in Zen Buddhism about your mindset when you capture art and make it into something. It’s a way to convey to someone a certain mental state, and not just an image.

I mentioned I did a bit of traveling after university. I was not following the news so much. I didn’t really know what I was getting myself involved into, but I went to Egypt right after graduating. I only knew the nuts and bolts, but this was while Mubarak was getting thrown out during the revolution. It was a very interesting experience being there and speaking with people.

I went to different places throughout Asia. Mongolia was another fascinating place that I think not a lot of people get to. Encountering people with different mindsets and worldviews, I started doing photography and blogging, to try to share with other people what that was like. And while living here in Japan [on the JET program], I continued blogging and wondered if there’s a way to make a career out of this.

I met some people around that time. Someone said, “You’ve got to meet this professor, David Holley.” I think he was the Los Angeles Times bureau chief in Beijing during the Tiananmen Square protests. He had a lot of experience in Japan and throughout Asia, and it was good to hear about the life that people further down the road lived.

I left Japan thinking, “Blogging and everything is great, but I want to become an actual journalist working for media companies.” That’s why I went back to the U.S. It wasn’t that I felt I was done living in Japan per se, but I applied to journalism schools in the U.S.

And this is where you and I met. My first job after the JET Program was with U.S.-Japan Council as a Communications Intern working with you. It was a short time, but I met really interesting people that are dedicated to bridging Japan and the U.S. While I was working with the U.S.-Japan Council, I got into the journalism schools that I applied to.

But I was thinking about these different, real connections that you’re trying to share through journalism. It was 2015, and in the midst of all this, there was a huge earthquake in Nepal. And I thought about the five months after university that I’d spent there, and what it means to learn how to be a journalist. I had nothing against formal education, but I thought about going to Nepal and telling stories about what impact that this had on the Nepali people and their resilience on the ground. So I abandoned my plans of journalism school in New York and went to Nepal instead.

I covered quite a bit in Nepal. I was volunteering with one hand— building temporary houses for people—and reporting with a camera in the other hand. I did a lot of reporting with VICE and got a lot of ideas for different stories from that time. That’s where my early-stage freelancing began.

I also covered a lot of stuff in Nepal that was unconnected to the earthquake. One was on the honey hunters of Nepal. We went to the Himalayas and did a documentary on Gurung villagers who harvest beehives the size of a kitchen table that are hanging on the side of cliffs. And we would watch people go down with bamboo ropes and collect honey like they’d been doing for hundreds of years.

It’s a different country, but the common thread in all my reporting is that anywhere you go, human beings are ultimately the same at heart. We just have very different manifestations of what we’re doing and different beautiful ways that we choose to live on the planet. Trying to capture that somehow is the common thread.

Above All Else, Listen

I love that philosophy. And I think it really shows through your storytelling, as well as the fact that you’re able to assimilate and become a part of these different cultures throughout the world.

I’d love to hear your perspective as a journalist. These communities that are often remote and rural may not have seen a lot of foreigners or outsiders. How do you build rapport with them so that they’re welcoming and willing to show you all these different things?

In terms of some areas being in the farther reaches of different places, with the Nepal honey hunter story, it was so remote that a lot of the Nepalese people that our team was with had difficulty communicating with them. Some of the local people didn’t speak Nepali. There are over 200 spoken languages in that country. And the media companies wanted signed release forms, but some of the villagers didn’t know how to write any script. So we got fingerprints instead.

But to answer your question about how to approach very rural or very different communities—I think it’s the same anywhere in the world. The bottom line is respect. And no matter where I go, my intention above all else is to listen. I’m not talking or trying to build a story.

The value that I see in journalism is twofold. One is to share with other people and try to impart some understanding of what’s taking place in the world. This is what media outlets are willing to fund. The other is—and they would probably never offer anyone a job for this—I love exploring these cultures and giving people the opportunity to share their stories.

Even if we found out that the camera wasn’t rolling or something, I feel like there’d still be a benefit in hearing this story and having this person be able to tell their story. It’s almost therapeutic for these people to share what they’re going through. But I think that as a journalist, you really set yourself apart if, above all, your main intention and your approach is one of respect.

The media industry has this demand where you have to leave with a certain finished product. And there’s all this budget involved to get there. A lot of journalists lose the human element of this, and see people as characters in the story. And when you view people as characters and not as individuals, it dehumanizes the art that it’s supposed to be all about humanizing the world. So I never try to lose sight of that no matter where I go.

At the end of the day, respect, respect, respect. That’s what I try to live by and do all my reporting with.

I really love your way of thinking, and I’m sure all your viewers appreciate that as well.

What stories are you most proud of? Could you name a few?

Sure. After the earthquake, there was this political tension on the border of Nepal. There’s this gray area. Borders are a very interesting place to tell stories. With this border between Nepal and India, people are not viewed as either—not fully Nepali or fully Indian. Many people in this area are actually stateless citizens. And there was a lot of tension that could be the subject of entirely different podcasts.

The fights for rights in this region of Nepal, which is called Terai, was something I did a lot of reporting on. And I’m proud of that early reporting where there were a lot of killings in protest taking place. Because of the language barrier, the foreign media that were reporting on this relied on locals to tell these stories. But I saw the way that, if you’re reporting on underprivileged communities, there might be a bias that comes about by hiring local people who are only able to get these positions of power because they are in a higher caste or a higher economic status. So I noticed the importance of being on the ground and really seeing things with your own eyes.

Right after being in Nepal, I went to Greece in 2015. It’s been in the news recently that Syrian President Assad was just taken out of power. 2015 was one of the peaks of the civil war that was taking place there. And this was the beginning of the huge migration of people from the Middle East coming into Europe.

So I went around different countries in Europe, and went to the doorstep where this was taking place. I went to Lesvos, a small island in Greece near Turkey. And on the border of [Central] Macedonia in Greece, there’s a small town called Idomeni. There were 10,000 refugees based there along the barbed wire fence, and they weren’t being let through to continue to other countries in Europe.

Speaking French and very elementary Arabic, I wanted to speak with people and understand what they were going through, as well as the different migration paths that they were on. Partly out of not having the budget and sponsorship from media outlets, and also just wanting to understand people on a deeper level, I camped out there with communities of journalists who were making an attempt to really embed and tell the stories of these people. So many media outlets were covering this at the time. It was difficult to pitch, both on an emotional level and because I was just getting started in journalism. That was something that I felt made a huge impact on me and the people I was reporting on.

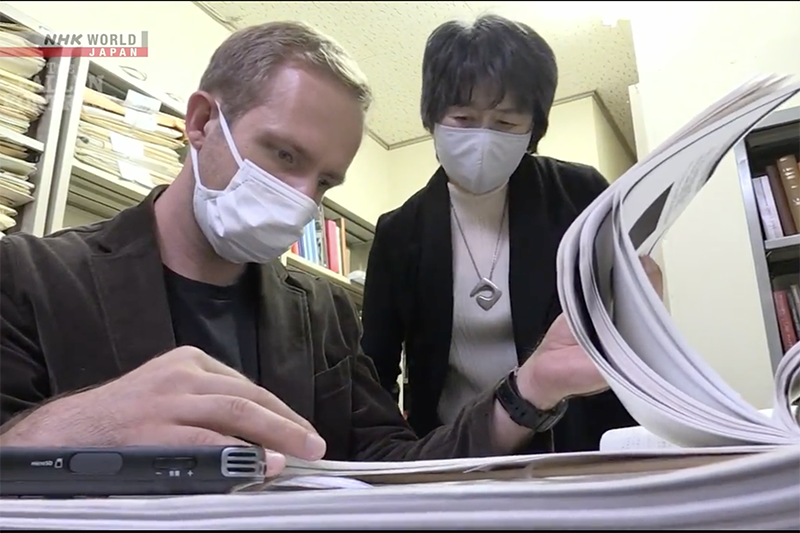

I’ll mention another story that consumed my life for the longest amount of time. It kind of became my life. I was researching this B-29 crash that had taken place in the village I was living in in Nara. I heard from a neighbor that there was an engine that was found on this hill. He said that a plane had gone down during World War II, but he didn’t know any details. I didn’t find anything through Google searches, and that motivated me to dig deeper. I filed requests with the U.S. National Archives. It wasn’t an easy process, but over the course of months, I found hundreds of pages of documents connected to this crash.

And I uncovered the amazing story of this plane that had gone down. It was an American B-29 that had flown over Japan for the bombing of Osaka. The plane had taken some flak over Osaka, and on the way back to Saipan, it crashed into the side of this Buddhist holy mountain called Mount Omine here in Nara.

Four individuals were able to parachute out. And I learned what happened with their story. I met people on the ground here in Japan who saw this take place when they were young elementary school students. These U.S. airmen were here to bomb Japan and were caught here. But before being taken into a POW camp, there was incredible kindness shown to them by some of the local villagers.

One person knew that they would have quite a difficult time if they were passed to the police or the village immediately. So they actually took them into their house and fed them strawberries that they had grown in their garden. One local doctor healed one of these soldiers, seeing that he was burned after the crash.

And again, going back to an earlier theme, we’re told these narratives that there might be certain people on this planet that are so different from us, or enemies, or just “the other.” But if you meet this “other” anywhere you go on planet Earth, it makes wars quite difficult to fight when you realize that at the end of the day, everyone is the same at heart and we’re all humans cut out of the same material.

So this story, for me: a) was very moving on an emotional level being able to share what had taken place and learn about all this, and b) [reminded me that] the further you get from World War II or any point in time, you have fewer people alive because of the nature of people passing away.

However, technology and the reporting methods that are available are also increasing. Documents that were top secret were made public, [and you can find them] if you know how to search for them. The U.S. has privacy laws where addresses of individuals can be public information4. And there’s this huge movement of digitization now of all these archival newspapers in the U.S., although it’s very far from complete. The U.S. National Archives has hardly anything digitized, but there is this very slow movement toward digitizing things where a human being physically scans every document.

There were 11 crewmen on this aircraft. I was able to able to track down all family members of all of them, and meet in person with individuals who didn’t know the details of how their brother, their father, their grandfather had passed away.

Wow…!

And there were a lot of really moving things that came out of that. There was a producer that I worked with while I was with NHK in New York. We worked together to produce a documentary on this on NHK World, which is called The Fallen Fortress. If you’re interested, it can be watched for free online. But yeah, that is definitely the story that maybe consumed my life the most in terms of investment and time. And it’s still not over. This year is the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II. So some loose ends are being tied up with that.

It really seems like you were meant to be the one to hear about this. You’re from the U.S., but you came to this very mountain where the B-29 crashed. And the fact that you were able to find family members is so moving because, as you said, it’s amazing timing where some of the confidential documents are becoming more public, but some of the family members are still alive. I’m sure they really appreciated your effort.

Yeah, these coincidences that take place in life will sometimes give you goosebumps with how wild they are. I’ve stopped getting surprised. It’s just atarimae5; of course this crazy thing would happen. You’ve just got to raise your antenna and be aware of all the different connections around you.

Freelancing vs. Working for an Organization

You mentioned that you had worked for major news organizations before, but I assume that working freelance gives you a bit more time to explore and dig deep into passion projects. You have to make a living, of course, so I’m sure it’s a difficult balance. But I think a lot of journalists would think that you’re living the dream, living abroad in a place of your choice and still working for all these major news corporations. Would you have any advice for any budding journalists who are interested in that lifestyle?

Whatever you’re doing, I think my advice is to just try and put in the time. There’s this idea that 10,000 hours is how long it takes to be proficient in any sort of thing. So in whatever kind of way you think is appropriate and will get you somewhere, put in the time and do the thing.

And I mentioned mostly the freelance stuff in terms of what I’ve done, the way I’ve got started, and what I’m doing now. But traditional media also played a big role in that.

There are advantages to working for institutions. You have this backing. I don’t think that we’ll ever see YouTubers and influencers filling all the seats in the White House press corps room or in the UN. There’s been some interesting examples where they’ve opened up. But I think that working for a mainstream media outlet gives you access that might be a lot more difficult to have as a freelancer, especially in Asia and Japan with the Kisha Club6 and the different types of restrictions that you might face.

My first traditional media roles were in New York. I worked with all Japanese media, but started with Tokyo Shimbun and Chunichi Shimbun, which have the same parent company. I worked for those and got started in print.

And then I moved across the street, just a few blocks away, working for NHK in New York. And it taught me a lot about dedication. Having other people really push you and drive you to do things that, working on your own, you might not have—having that education and learning from senpai7 or people who know more than you or have been in the field longer is a valuable experience.

It was fascinating working for Japanese media. I was essentially a foreign correspondent in my own country, the U.S. This was in 2016, when President Trump had won the first time, and all sorts of divisions were taking place in America. And we were going around the country trying to explain to Japanese viewers what America is and all these different slices of life.

And people would ask, “What media outlet are you? Are you left or right?” They try to figure you out. When we told them we’re working for Japan’s public broadcaster, it immediately disarmed them, and they saw that this is just someone who is trying to understand. So I think that foreign journalists working in the U.S. have an advantage of being able to show a sense of neutrality that might not exist with a domestic outlet.

But yeah, I’ve seen the benefits of that [working for major organizations]. My career has been alternating between working for traditional outlets and then going towards freedom, and like a jellyfish contraction and relaxing movement of swimming through the media sea.

Companies are evolving and coming and going all the time. My most recent semi full-time—”permalance” is another way to say it— job was working with CBS News in the Tokyo Bureau. And the Bureau closed after close to 60 years. They no longer have a presence. I guess Asia is not important!

But with all these changes in the field, you identify yourself less with a company and more as an individual in this effort. And you have to ask yourself these tough questions: What is it that I’m doing as a journalist? And what is the common thread? If it’s not the ship of this company, what is staying afloat and moving forward? And you have to develop this buoyancy and resiliency of certain ideals and values that keep you afloat and driving so that you don’t sink.

I really appreciate what you just said. I didn’t realize that being a foreign journalist is an advantage in this era of political division in the U.S. Earlier, you were talking about putting a human face on “the other.” And I think that’s critical, especially with so many big wars going on in different areas of the world. It’s all the more important to report what’s actually going on, as well as the voices of the local people. I just didn’t realize that at this point, that’s probably necessary within the U.S. as well. And there’s a lot of work to be done, for sure.

Kominka Life

Among the different countries that you lived in, why did you decide to choose Japan, and Yoshino in Nara Prefecture? Could you describe a little bit about the type of house that you’re living in, kominka8, which I think is a movement that’s really gaining traction in Japan?

Sure. When I was on the JET Program here, I found that TEDx talks were being held in Kyoto. I went and attended the talk of a man named Alex Kerr, an individual who’s been in Japan for the vast majority of his life. I think he came to Japan as a child in the 50s or 60s.

He gave a talk about reforming this farmhouse that he had found in the Iya Valley in Shikoku. And hearing his story, the history of the house and the love that he spent doing that, completely changed my life. I felt like this guy is doing something amazing and really valuing these traditional houses of Japan.

I don’t know if it’s been put in the English dictionary yet, but kominka is certainly a big buzzword that’s been going around. So is this other word, akiya. Akiya means “abandoned house.” It’s this huge crisis in Japan right now, where over 13% of all houses are abandoned. The other word, kominka, basically means “old house,” but these traditional houses that have been in Japan for hundreds of years are just incredible building structures.

I went back [to the U.S.] to work for Japanese media companies in New York for three years. And that whole time, I knew I couldn’t go back to the past and be a JET again, but I couldn’t really shake the feeling like I had a home in Japan. [I missed] the lifestyle here, the culture of respect, and just how everything in Japan works, especially coming from the U.S. where a lot of things don’t work. It just felt like a really nice place to live with really great people. That’s what made me want to come back here.

Also, the diversity both in Japan and in Asia—one thing I found is that there are so many different countries and very diverse cultures in the Asia Pacific region, even though it is a small area. So this is not necessarily a move to Japan, but a move to the Asia Pacific neighborhood.

Japan is around the size of the U.S. state of California, but there’s just so much diverse history and culture to explore that you can’t go through all of them in a lifetime. And it’s probably the only place that I’ve had this feeling to that degree, where I always have more to learn, and every day can be an experience to learn something new.

I also recognized that a lot of stories told about Japan and Asia are very superficial and not very authentic, like “China’s scary” or “Japan’s strange.” I found some pretty deep slices of life here that I felt were worth sharing, and that’s what made me want to come back.

In terms of why I’m living in a kominka in Yoshino, where I’m speaking to you right now, there are so many different parts to that. One is that these houses are beautiful, and a lot of areas with kominka are under threat of rural depopulation. There was a report released last year that over 40% of all municipalities in Japan are under threat of extinction. A lot of these areas will be turning into ghost towns if new people aren’t moving in.

But one thing that I’ve recognized is that there are new people moving into these villages. Maybe not enough to completely offset the rural depopulation that has taken place, but the cost of housing out here is low. The average cost of a house last year in the United States, I believe, was over 450,000 U.S. dollars. Here in Japan, a lot of these kominka are selling for 20,000 to 50,000 USD. For under 100,000 USD, you can live in a very beautiful and already livable house.

And that turned things upside down for me. I found that working in the U.S., especially recently, a lot of data shows that it’s a lot harder to get by now than it used to be in previous generations. I’m not a determinist and fatalist, and I’m not going to complain about my situation. But the fact is, it was a lot easier to live the dream of having a house and a stable job that you could depend on for decades and offered a pathway for growth. I just felt like a lot of that is gone.

I have nothing against the U.S. I love the life that I lived there. I still go back and consider that a big part of my identity. But in a lot of ways, it felt like treading water and running on this treadmill, wondering if you’re ever really going to get a sense of footing. And in many ways, it felt reactive, working for someone else to try to build a little island for yourself that you can stand on.

In Japan, through this kominka movement, I found beautiful architecture, the beauty of these communities and everything. That’s one part of it.

Aside from that, from an economic sense, for hundreds and thousands of years, humans were agricultural peasants living in different countries. In the 1900s, there was this big movement where people felt that moving to the city was a way to escape that. There was this huge move away from rural areas all around the globe. And to succeed and excel meant to be in the dynamo or the hive where everything is happening.

And now with remote work, especially with freelance work in media and shifts of the workforce, the security that was offered through living in a city may not be offered as much as it used to be. I find that people are able to take charge and be their own dynamo rather than moving to the center of where things are.

And that’s what I saw in moving to rural Japan: this ability to live in a very unique area with very unique history and very beautiful communities of people. We live in an era now where we can choose where we want to live and bring our work for a lot of different industries. That felt very empowering in many ways.

In the past 5-10 years, I’ve met an incredible number of both Japanese and non-Japanese people who have moved to Japan’s countryside to: a) live in these fantastic communities that have hundreds of years of history, and b) take charge and feel like they have some ground to stand on.

And these buildings are fantastically beautiful. I’ve met people that came to tears talking about the different ways the shiguchi9 wood joinery would come together, and the experience of meeting the carpenters that built these traditional houses. They are mostly built out of natural materials that go right back to the earth. It just feels like Japan’s doing a lot right, and I try to be a part of that in any way I can.

It’s really comforting to learn that there are places where you can feel unity with nature and the community, etc., but at the same time bring your global perspective and work as a journalist. I’m sure you have to commute a lot to Tokyo, Osaka, and other areas, but you have this great balance in your life, and it sounds really grounding.

Would you be staying there, or do you think you might move around to other areas in the Asia Pacific region? Do you have any plans for the future?

I’m now in a remote area in the hills of Yoshino. But no matter where you are in Japan, you’re never really that remote. I’m just an hour and a half away from Osaka by train. And they have an international airport right there. From a journalistic standpoint, I’m not in Yoshino as much as I am in Japan or the Asia Pacific. And this is a hub for me where I’m able to travel wherever I need to go.

I do go to Tokyo quite a bit, and wherever I need to be for storytelling. I also spend a lot of time going back and forth to the U.S., where my parents are. I think I’ll always have a foot in Yoshino, whether or not it’s living here full time every day of the month.

Life has many chapters, and I’ll take life one year at a time. Right now, it is my primary base when I’m not out reporting. I like it here. It’s a nice place to live.

I really love the way you think that it’s a chapter, because when we think about moving and where we want to be based, etc., it’s often such a big decision that you think, “What if I need to determine where to stay for the rest of my life?” But it’s not like that, and you can take it easy and see how things go.

Get Out There and Do It

Would you have any advice for others who might be struggling with big life decisions like finding their career or where they want to be based—especially people who are interested in working globally?

I think my main advice is to just follow what you think is right for you. Everyone is on their own path, and I don’t know if there’s a cookie-cutter way of living life and doing what’s right. There’s this word in Japanese called goen, meaning “connections that you feel with the world.” And I’m 100% about following places where I feel connections, such as areas where life feels the deepest or trying a different way of living.

For other people, I would prescribe the same thing. Do whatever feels right for you, and don’t force yourself to live internationally if you like living where you are. The world is increasingly much more global, and it’s easier to live a global life than it used to be. And hopefully [ticket prices for] flights will go down as technology increases. That’s one thing that is yet to catch up.

I call my parents all the time and am able to keep in touch. With the way technology has enabled us to stay together, you can feel like you’re not in a remote area or in another country.

There are a lot of challenges and technicalities, like the visa of living in another country. Or maybe the work that you want to get involved in isn’t something you can do remotely. That adds a lot of barriers too.

But try to think of places and ways that do work. For me, the nuts and bolts and the practical side of things are something I try to figure out after the fact. What’s the deeper goal, how do you get there, and how do you connect all the dots? It’s an “if there’s a will, there’s a way” kind of mentality. And so far, it’s been working for me. That’s what I’d recommend.

Well, thank you so much for that. The perspective that you have of technology and that it’s really all about your mentality—aside from where you are based, you can make the effort to communicate as much as you can and feel like others can rely on you, even if they’re far away—I think that’s so important.

I think that covers everything that I wanted to ask, but is there anything that you’d like to add?

I just think that life is short, but it’s also long. And so there’s no rush, and you should get out there and do all the things you want. The kind of people you will cross paths with and be exposed to is just amazing, if you’re willing to put yourself out there to the degree that you can.

Rather than thinking about security and feeling like you might tarnish your resume if you take a certain path or do a certain thing, think about how you can make the best impact on the world while you’re here and try to live according to that. See where it takes you. We’ve all got very interesting potential in us, so get out there and do all the things.

Thank you so much. That’s really helpful.

Thanks, Shiori.

Notes:

- Goen: Fateful connections. ↩︎

- Hanazono Jinja: A famous shrine in the Shinjuku area of Tokyo. ↩︎

- Taiko: Traditional Japanese drums. ↩︎

- Government records (like property ownership or voter registration) are generally considered public information in the U.S. This information can be found through general search or by accessing paid services. David often found relatives by searching for digitized obituaries of the airmen, looking up the contact information of relatives who are named, then cold calling or sending letters to them. He shares the backstory of one of the exceptions: “I had absolutely nothing on someone from a little town in Illinois, but I used Google Maps to see where I’d go out to eat dinner if I lived there, and after making a call to an Italian restaurant and asking them if they knew the relative, the owner told me (in shock that I was calling out of the blue from Japan) that they happened to be their high school classmate and put me in touch! Very bootstrap reporting methods, but [this way of] finding people’s names and addresses would not have been possible in countries like Japan that have much stricter national privacy laws.” ↩︎

- Atarimae: Japanese word meaning “natural.” ↩︎

- Kisha Club: Press club; Japanese association of journalists from specific media who are allowed to gather news from certain entities, like the Prime Minister’s Office. ↩︎

- Senpai: Senior colleagues. ↩︎

- Kominka: Traditional houses in rural Japan. ↩︎

- Shiguchi: Right angle wood joinery ↩︎